Translate this page into:

Effects of pharmaceutical promotions on antibiotics prescribing behavior of Nigerian private medical practitioners

*Corresponding author: Ifeanyichukwu Offor, PharmD, Department of Marketing and Product Development, Sun Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd., Lagos, Nigeria. ifeanyimega@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Offor I, Abubakar HF, Joda AE. Effects of pharmaceutical promotions on antibiotics prescribing behavior of Nigerian private medical practitioners. Am J Pharmacother Pharm Sci 2022;4.

Abstract

Objectives:

About 80% of pharmaceutical marketing efforts are directed toward physicians who are important decision-makers to patients’ medication needs. Pharmaceutical marketing can affect drug prescriptions, which, in turn, may adversely impact prescription practices. This study investigated the effect of pharmaceutical promotions on the antibiotic prescribing behavior of private practice physicians.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional and descriptive design was employed. Self-administered questionnaires, scaled on a linear 5-point Likert Scale, were distributed among 268 physicians attending the 44th annual scientific conference of the Association of Nigerian Private Medical Practitioners at Ibadan, in Southwest Nigeria.

Results:

The study achieved a response rate of 94%, and 243 completely filled questionnaires were included for data analysis using R version 4. Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the research instrument was found to be 0.991, indicating an excellent internal consistency. Most of the physicians were male (71%), medical officers (83%), and 49% were between the ages of 51 and 60 years. About 65% had over 20 years of practice experience. A majority, 211 (87%), have prescribed antibiotics under the influence of pharmaceutical companies’ promotions. However, Fisher’s exact tests demonstrated a weak association between relevant independent variables and the dependent variable (P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

Product detailing by pharmaceutical sales representatives was the most popular form of promotion and company-sponsored presentations had the greatest influence on the physicians’ prescription practice. It is, therefore, recommended that pharmaceutical promotions should be well regulated to guard against unethical practices.

Keywords

Pharmaceutical promotions

Prescription behavior

Private medical practitioners

INTRODUCTION

Pharmaceutical companies spend a huge amount of money on product advertisements and promotions, in hopes of convincing physicians to prescribe the product.[1] In 2015, the pharmaceutical industry spent an estimated USD 69.2 billion on various forms of pharmaceutical promotion and advertising in 31 countries.[2] Drug companies that deal with prescription drugs operate in a very competitive environment because of the existence of various brands of generic drugs. The competitive nature of the business environment makes it mandatory for them to develop and implement strong promotional strategies to gain and maintain a reasonable share of the market.[3] Most of the promotional strategies for prescription drugs include product detailing by pharmaceutical sales representatives, free drug samples, hospital unit meetings, gifting of branded promotional items, physicians’ sponsorship, scientific conferences, clinical trials, and journal advertisement, among others.[2,3] There may be a slight difference in the mode of execution of a strategy, depending on culture and existing pharmaceutical marketing regulations in a country. In the US, for example, the Sun Shine Act of 2007 which is now a part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act that mandates disclosure of payments and gifts to physicians has somewhat restricted pharmaceutical sales representatives’ physical visits to physicians.[4,5] As a result pharmaceutical companies are now devising other alternatives for reaching out to prescribers, including emails, direct mail, and peer-to-peer programs.[5] However, in emerging markets such as Nigeria, pharmaceutical sales representatives continue to directly visit prescribers to detail their products and lobby for prescriptions using various gift items and sponsorships to physicians.

The World Health Organization’s Geneva Convention of 1988 defined pharmaceutical promotion as “all informational and persuasive activities by manufacturers, the effect of which is to induce the prescription, supply, purchase, and/or use of medicines.”[6] In line with the WHO definition, evidence abounds to demonstrate that pharmaceutical promotions affect the physicians’ prescribing behavior.[2,7-9] Similarly, the previous studies report that several factors influence antibiotics prescribing behavior, including the physicians’ attitudes, patient-related factors, or health-care system-related factors. [10] However, there is a paucity of data on the influence of pharmaceutical promotion on antibiotics prescribing behavior.

Antibiotics are pharmacological agents that selectively kill or inhibit the growth of bacterial cells; while having little or no effect on the mammalian host.[11] They are categorized as prescription-only medicine – meaning that they can only be obtained from the pharmacy with valid prescription from a licensed medical practitioner.[12] This is why the primary target of pharmaceutical companies that sell antibiotics is physicians and other health-care practitioners. Inappropriate prescriptions of antibiotics have been faulted as a contributing factor to the increasing rates of antimicrobial resistance worldwide,[13] demanding a detailed study into what really drives physicians’ antibiotics prescribing behavior.

As pharmaceutical spending continues to escalate and drug safety becomes a key concern in pharmacotherapy, physician-directed outreach efforts have come under mounting public scrutiny.[14] Pharmaceutical firms, therefore, need to design their marketing strategies without affecting the ethical code of practice. Furthermore, drug companies need to understand how their marketing mixes influence the doctors’ choice of prescription drugs so as to know how to channel their marketing effort to achieve a good return on investment. Moreover, the knowledge of the effect of pharmaceutical promotions on prescription practices will be useful to policymakers and pharmaceutical regulators in designing educational interventions that will help foster rational antibiotics prescribing practices.[15] Therefore, the objective of this study is to assess the effects of pharmaceutical promotions on antibiotics prescribing behavior of private medical practitioners. Furthermore, it will evaluate, based on the physicians’ reports, which pharmaceutical promotional strategy is the most common or has the strongest influence on the physicians’ antibiotics prescribing behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and study participants

This study employed a cross-sectional, descriptive, and explanatory design. The study participants are Nigeria licensed private medical practitioners attending the 44th Annual General Meeting (AGM) and Scientific Conference of the Association of Nigerian Private Medical Practitioners (ANPMP), held in Ibadan the Oyo State Capital, in the southwestern part of Nigeria, from Tuesday March 22, 2022, to Saturday March 26, 2022. The ANPMP formerly called the Association of General and Private Medical Practitioners of Nigeria (AGPMPN) is a member of the world organization of family doctors, with over 5000 registered medical and dental practitioners practicing in different private facilities across Nigeria (Information from AGPMPN official website: https://www.agpmpn.org/structure.php). About 637 private medical practitioners from different parts of Nigeria attended the AGM, based on the conference attendance register.

Instrument for data collection and data analysis

The research instrument for this study is a self-administered and paper-based questionnaire which was adapted from the instrument used in a similar study.[16] The questionnaire is structured into two parts. The first part captured the demographic characteristics of the respondents while the second part of the questionnaire captured questions on pharmaceutical promotions and antibiotics prescribing behavior. The questions were close ended and the responses were scaled on a linear 5-point Likert scales, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree or from never to always. The values assigned were 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree and also 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = mostly, and 5 = always. To ensure that the research instrument is valid in the research environment, a standard questionnaire adopted from relevant literature sources was used, and the instrument was pretested on randomly selected 20 of the conference delegates to identify and correct any ambiguity, and the data included in the final analysis. The survey responses were all in anonymity so as to encourage the respondents to freely complete the questionnaire without withholding any information concerning their private practice. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha for all components of the questionnaire was computed. Relevant data from the questionnaires were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to check for accuracy. Thereafter, data were coded and loaded into R version 4 (Free Software Foundation’s GNU General Public License) for statistical analysis. The sample size was calculated using the Yamane Taro sample size formula.[17] Descriptive statistics on sample characteristics were computed. Categorical variables were presented in frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were tested for the assumption of normality to ensure the data follow normal distribution and justify the use of parametric test, while non-normal continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range. Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine if important covariates such as pharmaceutical promotions including pharmaceutical sales representatives, gifts and promotional items, free drug samples, advertisement in medical journals, sponsorship of clinical studies, peer promotions, and continuous medical education (CME) have statistically significant effect on the physician’s antibiotics prescribing behavior, and 95% confidence interval was computed for each predictor variable.

RESULTS

Reliability of the questionnaire

Cronbach’s alpha reliability test of the questionnaire was found to be 0.991, indicating an excellent internal consistency of this research instrument.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

The calculated sample size was 240 and a total of 252 questionnaires out of the 260 administered questionnaires were returned, giving a response rate of 94%. However, after screening the questionnaires for error and data editing, nine incompletely filled questionnaires were identified and discarded, thereby giving a final response rate of 93%. The remaining 243 valid questionnaires were included for final data analysis. There were 243 medical practitioners. The most of the physicians, 172 (71%) were male physicians and 118 (49%) were physicians between the ages of 51 and 60 years. Furthermore, 65% of the physicians had over 20 years of practice experience. The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in [Table 1]. However, a higher percentage (83%) of the medical practitioners was medical officers.

| Demographic characteristics | Frequency (n=243) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 71 (29) |

| Male | 172 (71) |

| Age (years) | |

| <34 | 10 (4.1) |

| >60 | 72 (30) |

| 35–40 | 3 (1.2) |

| 41–50 | 40 (16) |

| Years of practice (years) | |

| 6–10 | 7 (2.9) |

| 51–60 | 118 (49) |

| 3–5 | 5 (2.1) |

| 16–20 | 48 (20) |

| 11–15 | 29 (12) |

| >20 | 154 (63) |

| Category of facility | |

| General hospital | 6 (2.5) |

| Primary health center | 6 (2.5) |

| Private hospital | 227 (93) |

| Teaching hospital | 4 (1.6) |

| Designation | |

| Consultant | 34 (14) |

| Medical officer | 201 (83) |

| Professor | 2 (0.8) |

| Senior registrar | 6 (2.5) |

Pharmaceutical sales representatives

All the medical practitioners surveyed have met a pharmaceutical sales representative at least once in the past. A majority, 179 (74%), of physicians admitted that they have met a pharmaceutical sales representative at least once in the past. Furthermore, the majority (86%) of the physicians admitted that the pharmaceutical sales representatives are knowledgeable enough to provide drug information to medical doctors. More than half of the physicians, 165 (68%), trust the pharmaceutical sales representative on the correct dosage of antibiotics. However, 37 (15%) physicians agreed and 9 (4%) strongly agreed that pharmaceutical sales representatives should not be allowed to detail pharmaceutical products to medical doctors. The physicians’ responses to questions related to pharmaceutical sales representatives are presented in [Table 2].

| Questionnaire item on pharmaceutical sales representative | Overall, n=243 (%) | Consultant, n=34 (%) | Medical officer, n=201 (%) | Professor, n=2 (%) | Senior registrar, n=6 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have met a pharmaceutical sales rep before | |||||

| Always | 179 (74) | 23 (68) | 149 (74) | 2 (100) | 5 (83) |

| Mostly | 40 (16) | 6 (18) | 33 (16) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Sometimes | 24 (10) | 5 (14) | 19 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Rarely | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pharmaceutical sales rep are knowledgeable enough to provide drug information to medical doctors | |||||

| Strongly agree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 151 (62.1) | 24 (70.6) | 122 (60.7) | 1 (50) | 4 (66.6) |

| Neutral | 23 (9.5) | 2 (5.9) | 21 (10.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Disagree | 10 (4.1) | 1 (2.9) | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Strongly agree | 59 (24.3) | 7 (20.6) | 50 (24.9) | 1 (50) | 1 (16.7) |

| Pharmaceutical sales rep should not be allowed to detail to medical doctors | |||||

| Strongly agree | 9 (4) | 0 (0) | 9 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 37 (15) | 4 (12) | 31 (15) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) |

| Neutral | 50 (21) | 3 (8.8) | 47 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Disagree | 108 (44) | 22 (65) | 82 (41) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Strongly disagree | 39 (16) | 5 (15) | 32 (16) | 1 (50) | 1 (17) |

| I trust the sales rep to tell me the correct dosage of antibiotics | |||||

| Always | 16 (6.6) | 3 (9) | 13 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mostly | 62 (26) | 10 (29) | 49 (24) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Sometimes | 87 (36) | 13 (38) | 72 (36) | 1 (50) | 1 (17) |

| Rarely | 48 (20) | 3 (9) | 42 (21) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) |

| Never | 30 (12) | 5 (15) | 25 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Gifts and promotional items

The responses of the physicians to the questions on gifts and promotional items as presented in [Table 3] show that nearly all the physicians, 237 (98%), feel comfortable receiving non-cash gifts such as pens, writing pads, stethoscopes, textbooks, free lunch, or ward coat from a pharmaceutical company. Over 100 (42%) physicians admitting that they will always feel comfortable receiving these gift items from a pharmaceutical company. Furthermore, more than half (57%) of the physicians admitted that they will feel obliged to prescribe a pharmaceutical company’s product if the company gives them free sponsorship, gift, or promotional items. Moreover, a majority, 211 (87%), have prescribed antibiotics under the influence of pharmaceutical company’s promotions. On the contrary, however, 46 (18%) physicians admitted that it is not right for a medical doctor to receive gift items of any form from a pharmaceutical company.

| Questionnaire item (on gifts/promotional items and free drug samples) | Overall, n=243 (%) | Consultant, n=34 (%) | Medical Officer, n=201 (%) | Professor, n=2 (%) | Senior registrar, n=6 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I will feel comfortable receiving non-cash gifts such as pens, writing pads, stethoscope, textbooks, free lunch, and ward coat from a pharmaceutical company | |||||

| Always | 102 (42) | 19 (56) | 80 (40) | 2 (100) | 1 (17) |

| Mostly | 96 (40) | 9 (26) | 83 (41) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) |

| Sometimes | 39 (16) | 6 (18) | 32 (16) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Rarely | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I will feel obliged to prescribe a pharmaceutical company’s product if the company gives me free sponsorship, gift, or promotional items. | |||||

| Always | 45 (19) | 4 (12) | 37 (18) | 2 (100) | 2 (33) |

| Mostly | 44 (18) | 8 (24) | 34 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) |

| Sometimes | 49 (20) | 8 (24) | 40 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Rarely | 59 (24) | 8 (24) | 50 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Never | 46 (19) | 6 (18) | 40 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| It is not right for a medical doctor to receive gift item of any form from a pharmaceutical company | |||||

| Strongly agree | 18 (7) | 1 (3) | 17 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 28 (12) | 5 (15) | 23 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Neutral | 49 (20) | 6 (18) | 42 (21) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Disagree | 95 (39) | 18 (53) | 73 (36) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Strongly disagree | 53 (22) | 4 (12) | 46 (23) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| I have prescribed antibiotics based on pharmaceutical company’s promotional influence | |||||

| Always | 11 (5) | 1 (3) | 9 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Mostly | 38 (16) | 6 (18) | 29 (14) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Sometimes | 114 (47) | 15 (44) | 95 (47) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Rarely | 48 (20) | 9 (26) | 39 (19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 32 (13) | 3 (9) | 29 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Questionnaire item (on free drug samples) | Overall, n=243 | Consultant, n=34 | Medical officer, n=201 | Professor, n=2 | Senior registrar, n=6 |

| I will feel obliged to prescribe a company’s product if the company gives me free samples, provided that the product is effective and safe | |||||

| Always | 19 (8) | 0 (0) | 15 (7) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Mostly | 92 (38) | 13 (38) | 78 (39) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Sometimes | 67 (28) | 13 (38) | 51 (25) | 1 (50) | 2 (33%) |

| Rarely | 47 (19) | 7 (21) | 40 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 18 (8) | 1 (3) | 17 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I have received free samples of antibiotics from pharmaceutical companies | |||||

| Always | 12 (5) | 0 (0) | 11 (5.5) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Mostly | 41 (17) | 2 (5.9) | 35 (17) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) |

| Sometimes | 142 (58) | 23 (68) | 116 (58) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Rarely | 35 (14) | 7 (21) | 28 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 13 (5) | 2 (5.9) | 11 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| It is important that pharmaceutical companies give free samples for the physicians to check the efficacy | |||||

| Strongly agree | 55 (23) | 9 (26) | 40 (20) | 2 (100) | 4 (67) |

| Agree | 105 (43) | 12 (35) | 93 (46) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Neutral | 53 (22) | 6 (18) | 45 (22) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) |

| Disagree | 17 (7) | 4 (12) | 13 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Strongly disagree | 13 (5) | 3 (9) | 10 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pharmaceutical companies give free samples not for patients’ interest but to influence prescriptions | |||||

| Strongly agree | 10 (4) | 3 (9) | 7 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 30 (12) | 5 (15) | 24 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Neutral | 78 (32) | 13 (38) | 64 (32) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Disagree | 86 (35) | 9 (26) | 73 (36) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Strongly disagree | 39 (16) | 4 (12) | 33 (16) | 1 (50) | 1 (17) |

Free drug samples

The responses of the physicians to questions on free drug samples are also presented in [Table 3]. The information shows that 195 (80%) have received free antibiotics drug samples from a pharmaceutical company; with 180 (66%) admitting that it is important that a pharmaceutical company gives free samples for the physician to check its efficacy. On the contrary, only 40 (16%) medical doctors think that pharmaceutical companies give free drug samples not on patients’ interest but to influence prescriptions. Furthermore, 178 (73%) will be under obligation to prescribe a company’s product if the company gives them free samples, provided that the drug is perceived as effective.

Peer promotions and CMEs

[Table 4] shows the data on physicians’ responses to questions on peer promotions and CMEs. The dataset reveals that a majority of the physicians, 217 (89%), agreed or strongly agreed that pharmaceutical company’s product presentation is another form of CME, whereas 59 (24%) think that it is mere product marketing. Moreover, 172 (71%) physicians admit that there is nothing wrong if a medical doctor makes a product presentation on behalf of a pharmaceutical company. All the physicians admitted that they can advocate a pharmaceutical company’s product to their colleagues if they have good clinical experience with the product. Furthermore, 202 (83%) receive monetary honorarium from a pharmaceutical company for a speakership contract.

| Questionnaire item (on peer promotions/CMEs and Adverts in Medical Journals) | Overall, n=243 (%) | Consultant, n=34 (%) | Medical Officer, n=201 (%) | Professor, n=2 (%) | Senior registrar, n=6 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| There’s nothing wrong if a medical doctor makes a product presentation for a pharmaceutical company | |||||

| Strongly agree | 66 (27) | 13 (38) | 52 (26) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 106 (44) | 15 (44) | 87 (43) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) |

| Neutral | 59 (24) | 5 (15) | 52 (26) | 1 (50) | 1 (17) |

| Disagree | 12 (5) | 1 (2.9) | 10 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I can advocate a pharmaceutical company’s product to my colleagues if I have good clinical experience on the product | |||||

| Always | 129 (53) | 15 (44) | 111 (55) | 2 (100) | 1 (17) |

| Mostly | 84 (35) | 15 (44) | 65 (32) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) |

| Sometimes | 30 (12) | 4 (12) | 25 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Rarely | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I rely on information from my superiors, consultants, and teachers when prescribing antibiotics | |||||

| Always | 44 (18) | 8 (23) | 35 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Mostly | 53 (22) | 5 (15) | 44 (22) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Sometimes | 124 (51) | 14 (41) | 107 (53) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Rarely | 17 (7) | 5 (15) | 12 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 5 (2) | 2 (6) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I can receive monetary honorarium for a speakership contract with a pharmaceutical company | |||||

| Always | 49 (20) | 6 (18) | 40 (20) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Mostly | 66 (27) | 9 (26) | 54 (27) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Sometimes | 87 (36) | 15 (44) | 71 (35) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Rarely | 32 (13) | 2 (6) | 30 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 9 (4) | 2 (6) | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Pharmaceutical product presentation is another form of continuous medical education (CME) | |||||

| Strongly agree | 75 (30.9) | 12 (35) | 61 (30.3) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 142 (58.4) | 18 (53) | 119 (59.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (83) |

| Neutral | 8 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Disagree | 10 (4.1) | 3 (9) | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Strongly disagree | 8 (3.3) | 1 (3) | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pharmaceutical product presentations are mere product marketing | |||||

| Strongly agree | 17 (7.0) | 1 (2.9) | 15 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Agree | 42 (17) | 5 (15) | 34 (17) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) |

| Neutral | 36 (15) | 5 (15) | 30 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Disagree | 108 (44) | 15 (44) | 90 (45) | 2 (100) | 1 (17) |

| Strongly disagree | 40 (16) | 8 (24) | 32 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I rely on drug adverts in the medical journals when prescribing antibiotics | |||||

| Always | 11 (4.5) | 2 (5.9) | 9 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mostly | 32 (13) | 6 (18) | 23 (11) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) |

| Sometimes | 135 (56) | 16 (47) | 116 (58) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Rarely | 44 (18) | 7 (21) | 36 (18) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 21 (8.6) | 3 (8.8) | 17 (8.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Antibiotics should not be advertised on medical journals | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 43 (18) | 7 (21) | 34 (17) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 46 (19) | 10 (29) | 34 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) |

| Neutral | 57 (23) | 7 (21) | 48 (24) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) |

| Disagree | 97 (40) | 10 (29) | 85 (42) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) |

| Strongly disagree | 43 (18) | 7 (21) | 34 (17) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) |

| It is not right for clinicians to prescribe with brand names? | |||||

| Strongly agree | 14 (5.8) | 3 (8.8) | 11 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 71 (29) | 13 (38) | 56 (28) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) |

| Neutral | 45 (19) | 7 (21) | 38 (19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Disagree | 97 (40) | 11 (32) | 82 (41) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Strongly disagree | 16 (6.6) | 0 (0) | 14 (7.0) | 1 (50) | 1 (17) |

| I rely on the manufacturer’s prescribing information when prescribing antibiotics | |||||

| Always | 23 (9.5) | 4 (12) | 19 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mostly | 87 (36) | 12 (35) | 71 (35) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Sometimes | 106 (44) | 13 (38) | 89 (44) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Rarely | 27 (11) | 5 (15) | 22 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

CME: Continuous medical education

Adverts in medical journal

[Table 4] also captures data of the physicians’ responses to questions on medical journals. These responses show that 178 (73%) physicians rely on adverts on medical journal for the prescribing information of an antibiotic. However, the level of reliance on medical journal as source of antibiotics prescribing information varies among the doctors; with 18% admitting that they always or mostly refer to medical journal while 56% will sometimes use medical journal as source of antibiotics prescribing information. Furthermore, 40% disagree to the statement that “antibiotics should not be advertised in medical journals.” On the issue of prescribing antibiotics with the brand name, 85 (35%) physicians agreed that it is not right for clinicians to prescribe antibiotics with the brand name, but 113 (47%) have no issues with prescribing with brand names.

Sponsorship of clinical studies

Data on physicians’ responses to questions on sponsorship of clinical studies are presented in [Table 5]. The findings show that 149 (61%) physicians think that sponsorship of clinical studies by pharmaceutical companies may introduce bias in the study findings. Therefore, the majority (78%) of the medical doctors support the opinion that independent data monitoring committee should be appointed for all pharmaceutical companies sponsored clinical studies. Furthermore, 173 (71%) physicians admitted that sponsorship of a clinical study by pharmaceutical company in a particular hospital may increase the prescription of the company’s drug in that hospital.

| Questionnaire item | Overall, n=243 (%) | Consultant, n=34 (%) | Medical officer, n=201 (%) | Professor, n=2 (%) | Senior registrar, n=6 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sponsorship of clinical studies by pharmaceutical companies may introduce bias in the study findings | |||||

| Strongly agree | 10 (4.1) | 2 (5.9) | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 139 (57) | 18 (53) | 116 (58) | 1 (50) | 4 (67) |

| Neutral | 60 (25) | 7 (21) | 53 (26) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Disagree | 34 (14) | 7 (21) | 24 (12) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Independent data monitoring committee should be appointed for all pharmaceutical company’s sponsored clinical studies | |||||

| Strongly Agree | 30 (12) | 4 (12) | 24 (12) | 1 (50) | 1 (17) |

| Agree | 159 (65) | 22 (65) | 132 (66) | 1 (50) | 4 (67) |

| Neutral | 50 (21) | 7 (21) | 43 (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Disagree | 4 (1.6) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I rely on clinical findings of antibiotics in prescribing the drug. | |||||

| Strongly agree | 32 (13) | 7 (21) | 24 (12) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 141 (58) | 19 (56) | 118 (59) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) |

| Disagree | 14 (5.8) | 3 (8.8) | 11 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Neutral | 56 (23) | 5 (15) | 48 (24) | 1 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Disagree | 14 (5.8) | 3 (8.8) | 11 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

CME: Continuous medical education

The most common pharmaceutical promotional strategy

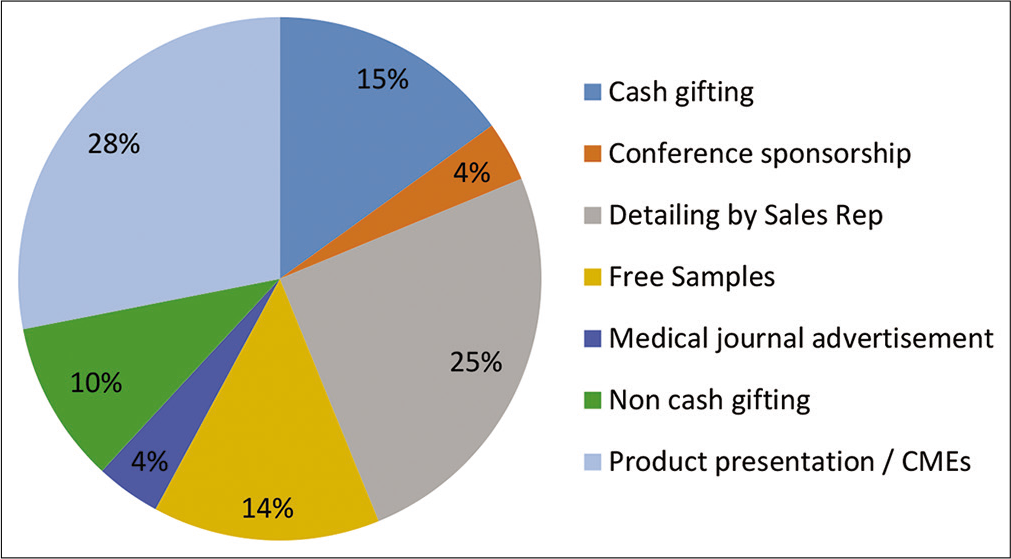

Data in [Figure 1] show that product detailing by pharmaceutical sales representatives is the most common form of pharmaceutical promotion across the various practice settings, based on the number of respondents to the question “which pharmaceutical promotion is the most common in your practice setting?”

- The most common pharmaceutical promotional strategies.

Level of influence of pharmaceutical promotions on physicians’ prescribing behavior

Data from [Figure 2] indicate that product presentation or CME by pharmaceutical companies has influenced on the antibiotics prescribing behavior of a higher percentage (28%) of physicians, followed by product detailing (25%), then cash gifting (15%), and free drug samples (14%). On the other hand, advertisements in medical journals and conference sponsorship have the least influence on the physicians’ prescribing behavior [Figure 2].

- Level of influence of pharmaceutical promotions on physicians prescribing behavior.

Correlation between pharmaceutical promotions and antibiotics prescribing behavior

Data from [Table 6] show the strength of the relationship between relevant independent variables (pharmaceutical promotions) and the dependent variable (prescription behavior).

| Variables | Overall, n=243 | Consultant, n=34 | Medical officer, n=201 | Professor, n=2 | Senior registrar, n=6 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverts in medical journals | 0.309 | |||||

| n | 243 | 34 | 201 | 2 | 6 | |

| Mean (IQR) (±SD) | 3.40 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.90) | 3.56 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.79) | 3.37 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.93) | 4.00 (4.00, 4.00) (±0.00) | 3.17 (3.00, 3.00) (±0.41) | |

| Pharmaceutical sales representative | 0.649 | |||||

| n | 243 | 34 | 201 | 2 | 6 | |

| Mean (IQR) (±SD) | 2.94 (2.00, 4.00) (±1.10) | 3.09 (3.00, 4.00) (±1.16) | 2.92 (2.00, 4.00) (±1.10) | 3.50 (3.25, 3.75) (±0.71) | 2.83 (2.00, 3.75) (±0.98] | |

| n | 243 | 34 | 201 | 2 | 6 | |

| Mean (IQR) (±SD] | 4.19 (4.00, 5.00) (±0.88) | 4.38 (4.00, 5.00) (±0.78) | 4.15 (4.00, 5.00) (±0.90) | 5.00 (5.00, 5.00) (±0.00) | 4.00 (4.00, 4.00) (±0.63) | |

| Pharmaceutical promotions | 0.107 | |||||

| n | 243 | 34 | 201 | 2 | 6 | |

| Mean (IQR) (±SD) | 2.79 (2.00, 3.00) (±1.01) | 2.79 (2.00, 3.00) (±0.95) | 2.75 (2.00, 3.00) (±1.02) | 3.50 (3.25, 3.75) (±0.71) | 3.67 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.82) | |

| Free drug samples | 0.127 | |||||

| n | 243 | 34 | 201 | 2 | 6 | |

| Mean (IQR) (±SD) | 3.19 (2.00, 4.00) (±1.07) | 3.12 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.84) | 3.17 (2.00, 4.00) (±1.10) | 4.00 (3.50, 4.50) (±1.41) | 4.17 (3.25, 5.00) (±0.98) | |

| Peer promotion | 0.632 | |||||

| n | 243 | 34 | 201 | 2 | 6 | |

| Mean (IQR) (±SD) | 3.47 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.94) | 3.35 (3.00, 4.00) (±1.18) | 3.48 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.90) | 3.50 (3.25, 3.75) (±0.71) | 3.83 (3.25, 4.00) (±0.75) | |

| Clinical study | 0.690 | |||||

| n | 243 | 34 | 201 | 2 | 6 | |

| Mean (IQR) (±SD) | 3.79 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.74) | 3.88 (4.00, 4.00) (±0.84) | 3.77 (3.00, 4.00) (±0.73) | 4.00 (3.50, 4.50) (±1.41) | 3.67 (3.25, 4.00) (±0.52) |

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study revealed that pharmaceutical promotions affect physicians’ antibiotics prescribing behavior. These data are also in line with results from related studies.[2,3,8,9] The present study also demonstrated that product detailing by pharmaceutical sales representatives is the most common form of pharmaceutical promotion while company-sponsored product presentation or “CME” has effect on the prescription practice of a greater number of the physicians. Ijoma et al.[3] in a similar study conducted in the southeastern part of the country reported that 60% of doctors who attended a company’s drug presentation felt influenced to prescribe the drug. Serhat et al.,[7] in a cross-sectional exploratory survey of primary health-care physicians in East Turkey, reported that the main source of prescribing information for majority (73.7%) of the physicians was commercial information provided by pharmaceutical sales representatives. Oshikoya et al.[18] are another questionnaire survey of medical doctors in a Nigerian teaching hospital observed that the physician used drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives as resources to determine their prescribing behavior. In our study, the majority of the physicians believe that the pharmaceutical sales representatives are knowledgeable enough to pass drug-related information to medical doctors. However, a previous study has shown that drug information provided by a pharmaceutical sales representative may not be completely accurate.[19] Mintzes et al.[20] in a prospective cohort study conducted in Canada, where a sample of primary care physicians was randomly recruited to report on sales visit of pharmaceutical companies’ staff, using a structured questionnaire, noted that a pharmaceutical sales representative, in an effort to influence the physician’s prescription, may downplay or skip the untoward effects of a drug when detailing the product to the physician. More also, pieces of evidence abound to show that interactions of physicians with pharmaceutical sales representatives may reduce prescription quality. A systematic review of 58 studies revealed that information provided by pharmaceutical company did not improve physicians’ prescribing but rather was associated with higher prescribing frequency, higher costs, or lower prescribing quality.[21]

Our findings revealed that most physicians will feel comfortable receiving non-cash gifts from pharmaceutical companies, and this places the physician under obligation to prescribe the drug company’s product. This is also in line with literature evidences that accepting gifts from pharmaceutical companies influence doctors’ prescriptions.[22] Giving free samples of a drug product to a physician can influence the prescription of that product. The most of the respondents in this survey admitted that they have received free antibiotics samples from a drug company and also felt obliged to prescribe same drug because of the free drug sample. It is believed that drug samples are among the most effective marketing tools that pharmaceutical companies have. A similar study has shown that giving physicians drug samples every week or fortnightly, provides pharmaceutical sales representatives the opportunity to interact directly with the physicians.[18] Usually, the argument supporting the use of free drug sample is that it gives the physician opportunity to confirm the efficacy and safety before using it.[23]

Sponsorship of clinical studies and drug advertisement in medical journals is also important promotional strategies of drug companies. Pharmaceutical companies sponsor clinical studies as a way of gaining prescribers confidence for that product. Our respondents supported the opinion that an independent data monitoring committee should be appointed for any pharmaceutical company-sponsored drug study. The most of the drug company-sponsored studies are primarily for marketing purposes.[19] The majority of the physicians in this survey rely on product advertisements on medical journals as their source of antibiotics prescribing information. However, a previous study reported that printed advertisement does not meet regulations and guidelines in various countries.[2]

In recent times, unethical pharmaceutical promotions have been a topic of concern among health-care fraternities. There have been several litigations and court cases bordering on wrong pharmaceutical promotions such as false claims and off-label promotions where the erring pharmaceutical companies were slammed with heavy fines running into billions of dollars. In the US, court cases involving multinational pharmaceutical companies have uncovered a range of promotional activities raising strong ethical and public health concerns.[24] A few of such litigations involving big pharmaceutical companies are mentioned below. In 2010, two subsidiaries of Johnson and Johnson, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical and Ortho-McNeil-Janssen, agreed to pay more than USD 81 million to settle all civil and criminal liability as a result of the companies’ illegal marketing of its anti-epileptic drug.[25] Furthermore, in the previous year, according to information from the US Department of Justice, another pharmaceutical giant, Pfizer in what was the largest pharmaceutical settlement in the U.S. history as at that time, reached a USD 2.3 billion settlement with the Department of Justice to resolve criminal charges and civil claims under the False Claims Act, for promoting four of its medicines outside the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved indications.[26]

Pharmaceutical companies are business organizations and so deserve to make profit to offset operational costs to keep their business running. The profits of pharmaceutical companies are heavily dependent on marketing and promotional activities, which are key factors driving sales volumes. However, when product sales are given priority over public health, promotion can lead to over-prescribing as well as poor quality prescribing and medicine use. This, in turn, may lead to an increased risk of adverse effects and higher health-care costs. It is important, therefore, to regulate pharmaceutical marketing communications and promotional activities to ensure good marketing ethics and the protection of patients’ interests at all times. Pharmaceutical marketing communications are regulated by appropriate regulatory agencies in different countries. For example, in Nigeria, there is the “National Agency for FDA and Control” (NAFDAC) which regulates the advertisement of all pharmaceutical products.[12] In the United Kingdom, there is the “Medicine and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency” performing similar roles like NAFDAC in Nigeria,[27] while in the US, the Federal Trade Commission is responsible for regulating all “OTC” drug advertisement, and the FDA regulates advertisement of prescription drugs.[28]

Our study is not without limitations. First, it employed self-administered questionnaires as the research instrument. This may represent a potential limitation to the study findings because the possibility of bias in the responses to the questions cannot be completely ruled out. A majority (30%) of the physicians in this study were over 60 years old. The ability of the physicians to completely recall how, or to what extent their interactions with pharmaceutical sales representatives affected their prescribing practice in the past may also be a potential bias to the present study. The influence of drug promotion on physicians has been noted as one of the difficult research areas because the most of the physicians are either not aware of how far-reaching the effects of drug promotion could be on them or they simply downplay the effects.[3] Therefore, the future research in this area should incorporate direct prescriptions audit in the methodological design. Second, Fisher’s exact tests demonstrated a weak association between relevant independent variables (pharmaceutical promotions) and the dependent variable (antibiotics prescribing behavior) (P > 0.05). This weak association does not nullify the hypothesis “that pharmaceutical promotions affect physicians prescribing behavior” because majority of the respondents in this study agreed or strongly agreed that pharmaceutical promotions influence their prescription practice. It is important to note also that Fisher’s exact test has some limitations. Some authors have argued that it is conservative and that its actual rejection rate is below the nominal significance level.[29]

CONCLUSION

Pharmaceutical promotions affect antibiotics prescribing behavior of private medical practitioners. Company-sponsored product presentation was identified as having the strongest influence on physicians’ prescription behavior, while product detailing by pharmaceutical sales representatives is the most common form of the pharmaceutical promotion. Therefore, it is important to regulate pharmaceutical promotions, especially the activities of pharmaceutical sales representatives to guard against unethical practices.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- General public knowledge, perceptions and practice towards pharmaceutical drug advertisements in the Western region of KSA. Saudi Pharm J. 2014;22:119-126.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug promotional activities in Nigeria: Impact on the prescribing patterns and practices of medical practitioners and the implications. Hosp Pract 1995. 2018;46:77-87.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of promotional strategies of pharmaceutical companies on doctors' prescription pattern in South East Nigeria. TAF Prevent Med Bull. 2010;9:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physicians-pharmaceutical sales representatives interactions and conflict of interest: Challenges and solutions. Inquiry. 2016;53:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nearly Half of US Physicians Restrict Access by Manufacturer Sales Reps New Strategies to Reach Physicians. A Rockpointe Publication. Available from: https://www.policymed.com/2013/10/nearly-half-of-us-physicians-restrict-access-by-manufacturer-sales-reps-new-strategies-to-reach-physicians.html Accessed 06 May 2018

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethical Criteria for Medicinal Drug Promotion. 1988. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: https://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/38125/924154239X_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0D1796BE4677CB3C27D6B9A96676CF37?sequence=1 [Last accessed on 2021 Aug 09]

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of pharmaceutical promotion on prescribing decisions of general practitioners in Eastern Turkey. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:122.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A follow-up study on the effects of an educational intervention against pharmaceutical promotion. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240713.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do drug company promotions influence physician behaviour? West J Med. 2001;174:232-233.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding physician antibiotic prescribing behaviour: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41:203-212.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Principles of antibiotic therapy. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2009;9:184-188.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drugs and Related Products Advertisement Regulations. Available from: https://www.nafdac.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/files/resources/regulations/regulations_2021/drug-and-related-products-advertisement-regulations-2021.pdf Accessed 09 Aug 2021

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial Resistance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance [Last accessed on 2021 Aug 09]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of physician-directed pharmaceutical promotion on prescription behaviors: Longitudinal evidence. Health Econ. 2017;26:450-468.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interventions to improve antimicrobial prescribing of doctors in training: The IMPACT (Improving antimicrobial prescribing of doctors in training) realist review. Br Med J Open. 2015;5:e009059.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmaceutical marketing to medical students: The student perspective. McGill J Med. 2004;8:21-27.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sources of drug information and their influence on the prescribing behavior of doctors in a teaching hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;9:13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How drug companies manipulate prescribing behavior. Colomb J Anaesthesiol. 2018;46:317-321.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmaceutical sales representatives and patient safety: A comparative prospective study of information quality in Canada, France and the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1368-1375.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians' prescribing: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000352.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General practitioners and sales representatives: Why are we so ambivalent? PLoS One. 2022;17:e0261661.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of patients receiving pharmaceutical samples and association between sample receipt and out-of-pocket prescription costs. Med Care. 2008;46:394-402.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The lessons of vioxx-drug safety and sales. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2576-2578.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Makers to Pay Fine of $81 Million. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/30/business/30fine.html Accessed on 29 Apr 2020

- [Google Scholar]

- Justice Department Announces Largest Care Fraud Settlement in its History. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announceslargest-health-care-fraud-settlement-its-history accessed on 02 Sep 2009

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Blue Guide Advertising and Promotion of Medicines in the UK. 2020. London: Medicine and Health Regulatory Agency; Available from: https://www.assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/956846/bg_2020_brexit_final_version.pdf [Last accessed on 2021 Aug 09]

- [Google Scholar]

- Prescription Drug Advertising Questions and Answers. United States: US Food and Drug Administration; 2015. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/prescription-drug-advertising/prescription-drug-advertising-questions-and-answers#control_advertisements [Last accessed on 2021 Aug 09]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In dispraise of the exact test: Do the marginal totals of the 2 x 2 table contain relevant information respecting the table proportions? J Stat Plan Inference. 1978;2:27-42.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]