Translate this page into:

Individualized patient care and clinical outcomes in HIV/AIDS management

*Corresponding author: Unyime Israel Eshiet, PhD Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Biopharmacy, University of Uyo, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. unyimeeshiet@uniuyo.edu.ng

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Eshiet UI, Njoku CR. Individualized patient care and clinical outcomes in HIV/AIDS management. Am J Pharmacother Pharm Sci 2023;017.

Abstract

Objectives:

Individualized care has the potential to significantly improve health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions. This study was aimed at evaluating the quality of individualized care and its impact on clinical outcomes in patients with the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) receiving treatment in a resource-limited setting.

Materials and Methods:

The study was a cross-sectional prospective study carried out in the HIV/AIDS clinic of the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Data on the demographic and clinical details of the patients were obtained from patient’s case notes using a suitably designed, pre-piloted data collection instrument. Data on patients’ assessment of the quality of individualized care were obtained using a “Patient Assessment of Quality of Individualized Care for Chronic Illness Scale.” Quantitative data were analyzed using the IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions version 25.0 computer package. Descriptive statistics was used to summarize data, whereas inferential statistics was used where applicable with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Results:

The overall mean patients’ satisfaction with individualized care score was 3.54 (standard deviation = ±0.86; max. = 5). The majority of the patients (271) had a documented viral load of <50 copies/mL, whereas 27% (109) of the patients had a recently documented CD4 count that was >500 cells/mm3. Bivariate analysis showed that the quality of individualized care was positively correlated with the patients’ CD4 count (r = 0.036; P = 0.657). A negative correlation between the quality of individualized care and the patients’ viral load (r = −0.103; P = 0.177) was also found.

Conclusion:

Provision of individualized care to patients with HIV/AIDS may improve clinical outcomes. In making therapeutic decisions, clinicians should take into cognizance individual patients’ preferences and needs.

Keywords

Individualized care

Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

CD4 count

Viral load

INTRODUCTION

Individualized care can be considered a turning point in health-care delivery. It entails putting into consideration the patient’s desires, lifestyles, social circumstances, values, and peculiar family situations in the provision of health-care services. It involves developing and implementing health-care services that put the patients and their families at the center of health-care decisions. It is focused on meeting patients’ individual needs. In providing individualized care, clinicians view the patients as experts and work with them to achieve desired therapeutic outcomes.[1,2]

Individualized care does not imply giving the patients whatever they want, but it involves seeing the patients as equal partners in developing, implementing, and monitoring health-care services. In providing individualized care, health-care providers should respect the views of the patients on issues of their health, take into account their expressed needs and preferences, and work with them to achieve treatment goals.[1,2]

The engagement of patients in the provision of care has been identified as an important component of clinical practice in many advanced health-care systems.[3,4] It is increasingly becoming a standard of care in many health-care settings and has been described as a proactive attempt by patients to bridge the gap between their expectations or preferences in the care relationship and what they experience during consultation with their health-care provider.[3,5] Research findings suggest that providing healthcare that suits patients’ preferences and needs results in improved treatment outcomes.[3,6-9]

To improve the involvement of patients in the delivery of healthcare, several approaches have been initiated by clinicians over the past years. A new approach termed “partnership in care” seeks to harmonize patients’ preferences and needs, their active participation in clinical decision-making, and the optimization of patients’ capacities for self-care in the provision of healthcare.[10] The application of the “partnership in care” approach to healthcare delivery entails recognizing patients as members of the healthcare team.

In the past, people were expected to fit in with the routines and practices that health-care services felt were most appropriate. However, with individualized care, health-care services are made less rigid and more flexible to accommodate patients’ preferences in a manner that is most appropriate for them. Such care can be provided to an individual patient on a one-to-one basis, or in groups. However, in both situations, the underlying philosophy is the same, that is working with the patient in the provision of health-care services.[11]

Research reports suggest that individualized care has the potential to significantly improve the quality of healthcare. These reports indicate that individualized care can positively impact on patients’ health outcomes and improve patients’ confidence and satisfaction with care.[11-13]

Literature on the impact of individualized care on treatment outcomes in patients living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is insufficient. Two previous studies have reported a positive association between the quality of patient–provider relationship and self-reported adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART),[14,15] which provides strong preliminary evidence that interpersonal aspects of healthcare may directly correlate with the health of patients with HIV. These studies were carried out in countries with advanced health-care systems. Reports of similar studies from developing countries with less advanced health-care systems appear to be lacking. This study was carried out in Nigeria and was aimed at evaluating the quality of individualized care as perceived by patients and its impact on clinical outcomes in persons living with HIV/AIDS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

A cross-sectional prospective study was conducted using suitably designed and validated instruments to extract data from patients living with HIV/AIDS receiving treatment at the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital (UUTH), in Uyo, Nigeria. Study participants were recruited from the antiretroviral clinic of the hospital.

Data on the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were obtained from patients’ case notes using a suitably designed, pre-piloted data collection instrument. Data that were collected from the case notes included:

Gender

Patient’s age

Education level

Duration of illness

Presence of comorbidity

Type of comorbidity (if present)

Documented CD4 count

Documented viral load.

Furthermore, data on patient-perceived quality of individualized care were obtained using a “patient assessment of quality of individualized care for chronic illness scale.”

Study population/sample size

All patients with HIV/AIDS who met the eligibility criteria were recruited into the study.

The eligibility criteria for recruitment into the study were:

Patients diagnosed with HIV/AIDS and receiving treatment at UUTH within the period of the study

Patients who expressed willingness to participate in the study

Patients who provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

The exclusion criteria were:

Patients <18-years-old

Patients with active psychiatric illnesses

Patients who were not able to communicate effectively in the English language.

The sample size was determined by using the formula described by Yamane.[16]

n = N/1+N (e2)

Where n = calculated sample size; N = population of HIV/AIDS patients that attended clinic within the period of the study; e = level of precision (± 5%).

Data collection instruments

Patient assessment of the quality of individualized care for chronic illness scale

The Patient Assessment of Quality of Individualized Care for Chronic Illness Scale is a 5-item self-administered questionnaire designed by researchers from literature searches,[17-21] validated and used to evaluate the quality of individualized care provided.

The developed questionnaire was reviewed by a team of expert panels composed of clinicians practicing in the academia, hospital, and community. This was done to confirm content validity. These experts reviewed the questionnaires individually and rated them based on four categories (content relevance, clarity, simplicity, and ambiguity). All the comments from the content and face validation were thoroughly discussed by the research team. The items were either edited, removed, or remained unchanged after extensive discussion among the researchers.

Furthermore, a pilot test was carried out on the revised questionnaire to assess the readability and general formatting of the questionnaire. This was done using 20 randomly selected patients living with HIV/AIDS.

The higher the score on the patient assessment scale, the higher the quality of individualized care provided (a “yes” response to each question on the scale attracted a score). Furthermore, a scoring template was used to grade the patient assessment scores into different levels of individualized care with scores of <3 indicating a poor level of individualized care, and scores of 3 and ≥4 indicating a moderate and high level of individualized care, respectively.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using the IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions version 25.0 computer package (IBM Corp, version 25.0 Armonk, NY and USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data, whereas inferential statistics such as bivariate Pearson correlation and multivariate linear regression were used to test the relationship between assessment variables. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the UUTH (UUTH/AD/S/96/ VOLXXXI/580). In addition, written informed consent was obtained from the participants and strict confidentiality was ensured during the data collection and handling.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

Four hundred patients with HIV/AIDS who met the inclusion criteria were recruited into the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 127 | 31.75 |

| Female | 273 | 68.25 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 19–25 | 16 | 4.00 |

| 26–35 | 86 | 21.50 |

| 36–45 | 144 | 36.00 |

| 46–55 | 93 | 23.25 |

| 56–65 | 48 | 12.00 |

| >65 | 13 | 3.35 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary | 72 | 18.00 |

| Secondary | 185 | 46.25 |

| Tertiary | 143 | 35.75 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 393 | 98.25 |

| Islam | 7 | 1.75 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 122 | 30.50 |

| Married | 213 | 53.25 |

| Separated | 16 | 4.00 |

| Widowed | 49 | 12.25 |

| Duration of illness | ||

| <1 year | 24 | 6.00 |

| 1–5 years | 120 | 30.00 |

| 6–10 years | 111 | 27.75 |

| 11–15 years | 113 | 28.25 |

| 16–20 years | 29 | 7.25 |

| >20 years | 3 | 0.75 |

| Presence of comorbidity | ||

| None | 305 | 76.25 |

| Yes | 95 | 23.75 |

| Type of comorbidity | ||

| HTN | 70 | 73.68 |

| DM | 9 | 9.47 |

| HTN and DM | 6 | 6.32 |

| Others | 10 | 10.53 |

HTN: Hypertension, DM: Diabetes mellitus

About 36% of the patients had been receiving care for HIV/AIDS for over 10 years, whereas about 24% of the patients had other comorbidities with hypertension being the most frequently reported comorbidity in this population.

Patients’ assessment of the quality of individualized care

About 90% of the patients with HIV/AIDS were satisfied with the individualized care they received from their health-care providers, and 90% of the patients affirmed that their health-care providers knew and treated them as a person not just as a patient.

The item-by-item mean patients’ assessment scores for individualized care based on the Patient Assessment of Quality of Individualized Care for Chronic Illness scale are presented in [Table 2].

| S. No. | Questions on the scale | Yes n (%) |

No (%) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | My health-care providers in this clinic know me as a person. | 361 (90) | 39 (10) |

| 2. | My health-care providers in this clinic are genuinely interested in my health and general well-being. | 380 (95) | 20 (5) |

| 3. | My health-care providers in this clinic usually ask for my ideas/ suggestions before initiating a treatment plan. | 239 (60) | 161 (40) |

| 4. | My health-care providers in this clinic encourage me to talk about any problems with my medicines or their effects. | 356 (89) | 44 (11) |

| 5. | I am satisfied with the care provided by my health-care providers in this clinic. | 360 (90) | 40 (10) |

The overall mean patient assessment of individualized care score was 3.54 (±0.86) [Table 3].

Based on the deduced patients’ assessment of individualized care level, where patient assessment scores of <3 was considered a low level of individualized care, with patient assessment scores <3 and ≥4 were considered moderate and high levels of individualized care, respectively, we found that in 68.5% (274) of the cases studied a high level of individualized care was provided [Table 3].

| S. No. | Assessment score level | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Low level | 34 | 8.5 |

| 2. | Moderate level | 92 | 23.0 |

| 3. | High level | 274 | 68.5 |

Overall mean patient assessment of individualized care score=3.54 (±0.86)

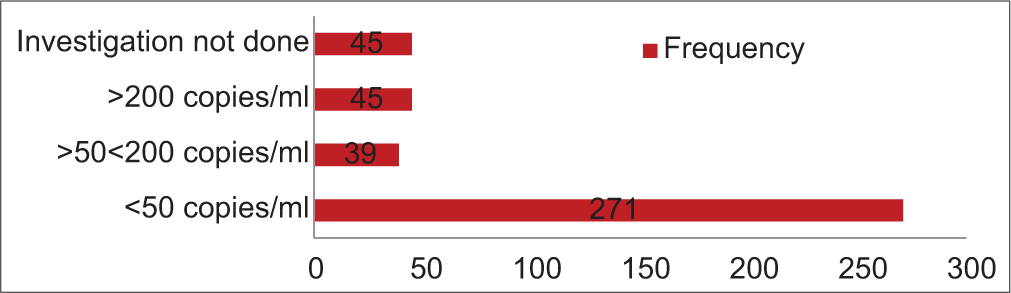

Patients’ viral load

The majority of the patients (271) had a documented viral load of <50 copies/mL. A chart showing the categorization of patients based on the viral load is presented in Figure 1.

- Chart showing patients’ CD4 count.

| Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| ≤200 cells/mm3 | 43 | 10.75 |

| >200<500 cells/mm3 | 119 | 29.75 |

| >500 cells/mm3 | 109 | 27.25 |

| Investigation not done | 129 | 32.25 |

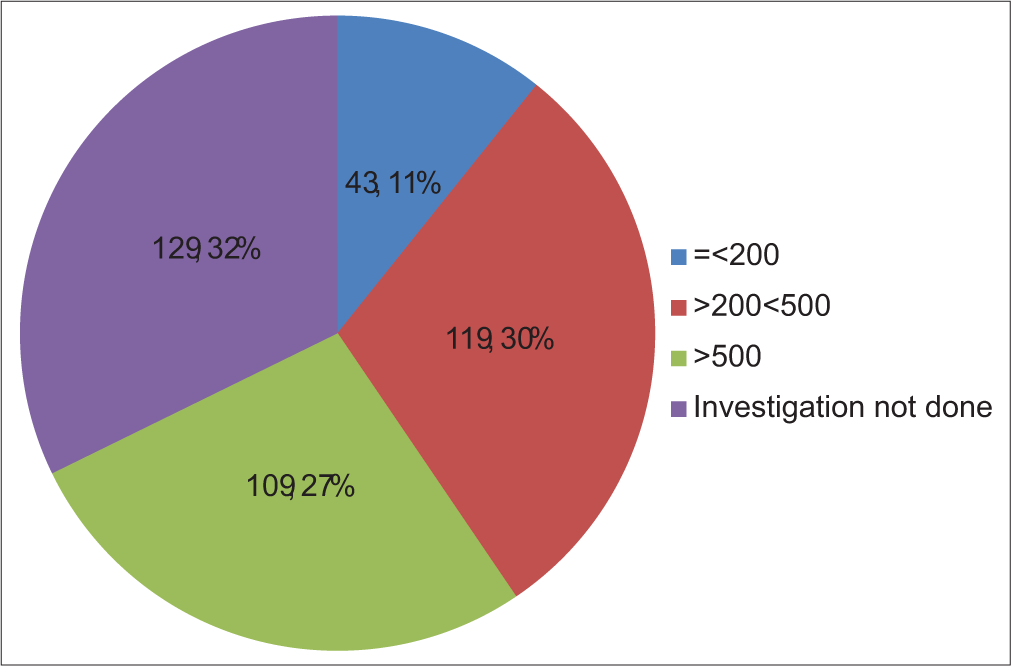

Patients’ CD4 count

Although we did not find a documented CD4 count in the majority (32.25%) of the cases studied, we found that about 27% (109) of the patients had a documented CD4 count that was >500 cells/mm3.

A chart showing the categorization of patients based on their CD4 count is presented in Figure 2.

- Chart showing patients’ human immunodeficiency virus viral load.

| Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| <50 copies/mL | 271 | 67.75 |

| >50<200 copies/mL | 39 | 9.75 |

| >200 copies/mL | 45 | 11.25 |

| Investigation not done | 45 | 11.25 |

Test of the relationship between the quality of individualized care and clinical outcome assessment variables

Correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship between the quality of individualized care and clinical outcome assessment variables. In this bivariate analysis, results showed that the quality of individualized care was positively correlated with the patients’ CD4 count (r = 0.036; P = 0.657) and a negative correlation between the quality of individualized care and the patients’ viral load (r = −0.103; P = 0.177) was also found indicating that a higher patients’ satisfaction with individualized care score results in a higher CD4 count and a lower their viral load among the patients. However, these associations were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

The provision of individualized care to patients has been widely viewed as the goal standard for high-quality interpersonal care.[1,2,18] We assessed the quality of individualized care from the perspective of 400 patients living with HIV/AIDS who received therapeutic care from a tertiary health-care facility in Southern Nigeria. We found as expressed by the majority of the patients that the quality of individualized care provided for patients with HIV/AIDS in the facility was high. Studies have shown that patients who report that their health-care providers demonstrate patient-centered care are generally more satisfied with the care provided and show significant improvements in their health outcomes.[2,11,22]

Personalized therapeutic care from health-care providers is associated with increased patient satisfaction and improved clinical outcomes in patients with chronic medical conditions.[11-13] Studies among patients with HIV have also reported that effective patient health-care provider relationship and communication can improve medication adherence.[23-25]

In the management of HIV/AIDS, strict adherence to HAART is essential to achieve therapeutic goals and prevent drug resistance and disease complications including death.[12] In general, the aim of the management of HIV/AIDS is to achieve an undetectable viral load and a high CD4 count. We observed that the majority of the population studied had a documented viral load level <50 copies/mL. In the management of HIV, viral load is commonly used to assess the disease progression and outcome of treatment. It is a measure of the number of HIV particles per mL of the patient’s blood. A viral load level of <50 copies/mL can be considered a treatment target by clinicians providing therapeutic care for patients with HIV/AIDS.[26]

Although we did not find appropriate documentation of CD4 count in the majority of the cases studied, we found that 27% of the study population had a recently documented CD4 count above 500 cells/mm3. CD4 counts >500 cells/mm3 are widely regarded as healthy. The CD4 count plays an essential role in a patient’s immune system and is widely used to assess the strength of a patient’s immune system. Thus, monitoring patients’ CD4 counts is important in the management of HIV/AIDS.

Although not statistically significant, we found a positive correlation between the quality of individualized care and the patients’ CD4 counts and a negative correlation between the quality of individualized care and the patients’ viral load. This finding provides an indication that providing quality personalized care to patients with HIV/AIDS may help improve their CD4 counts and lower their viral load. The association between the quality of individualized care and patients’ viral load and CD4 count as observed in this study may be attributed to a probable improvement in adherence to HAART that is associated with the provision of individualized care to patients with HIV/AIDS. A positive association between patient adherence to HAART and the quality of patient-provider relationship has been reported in previous studies.[12,27]

Beach et al., in a similar study on HIV patients, observed a significant association between the quality of the patient– provider relationship and having an undetectable serum level of HIV-1 RNA. However, they found that the association was no longer significant after adjusting for patient adherence to HAART, indicating that adherence to HAART was the primary mediator for the association between the quality of patient-provider relationship and suppression of HIV-1 RNA.[18]

In providing care to patients with long-term conditions such as HIV/AIDS the inclusion of patients’ views, better conversations with the patients, and making clinical decisions based on individual patients’ preferences, needs, and priorities will help keep the burden of treatment on the patients low, and improve patient acceptability and adherence to clinical recommendations.

CONCLUSION

The quality of individualized care offered to patients with HIV/AIDS in the facility as perceived by the majority of the study participants is high. The majority of the patients had HIV-viral load within the treatment target. The provision of individualized care may improve clinical outcomes in patients living with HIV/AIDS. In making therapeutic decisions, particularly for chronic medical conditions, clinicians should take into cognizance patients’ individual social circumstances, preferences, lifestyles, values, and needs.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

References

- Developing instruments to measure the quality of decisions: Early results for a set of symptom-driven decisions. Patient Educ Counsel. 2008;73:504-510. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.009

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient engagement: An investigation at a primary care clinic. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:85-98. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S42226

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient engagement in care: A scoping review of recently validated tools assessing patients' and healthcare professionals' preferences and experience. Health Expect. 2021;24:1924-1935. doi:10.1111/hex.13344

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of patient involvement on clinical practice guideline development: A parallel group study. Implement Sci. 2018;13:55. doi:10.1186/s13012-018-0745-6

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patients as partners: A qualitative study of patients' engagement in their health care. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122499. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122499

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288:2469-2475. doi:10.1001/jama.288.19.2469

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ. 2002;325:1263. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1263

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient-reported outcomes and the evolution of adverse event reporting in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5121-5127.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving the outcomes of disease management by tailoring care to the patient's level of activation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:353-360.

- [Google Scholar]

- The patient-as-partner approach in health care: A conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad Med. 2015;90:437-441. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000603

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient-centered approaches to health care: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:567-596. doi:10.1177/1077558713496318

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: A review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:51-61. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00099-X

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of person-centred care as an intervention in controlled trials-a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:456-465. doi:10.1111/jocn.12039

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sociodemographic and psychological variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:1763-1769. doi:10.1097/00002030-199909100-00021

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:756-765. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11214.x

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Determining sample size, Publication of the agricultural education and communication department, Florida cooperative extension service In: University of Florida: Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1096-1103. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30418.x

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:661-665. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of patient-centered care on patient satisfaction and quality of care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2008;23:316-321.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- What is patient-centred care and why is it important? Available from: https://www.hin-southlondon.org [Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Helping measure person-centred care-a review of evidence about commonly used approaches and tools used to help measure person-centred care. 2014. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/helpingmeasurepcc [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 23]

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient centred care made simple. 2016. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/personcentredcaremadesimple.pdf [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 15]

- [Google Scholar]

- Towards a global definition of patient centred care: The patient should be the judge of patient centred care. BMJ. 2001;322:444-445. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person-centred care and job satisfaction of caregivers in nursing homes: A systematic review of the impact of different forms of person-centred care on various dimensions of job satisfaction. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:219-229. doi:10.1002/gps.2719

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International alliance of patients' organizations perspectives on person-centered medicine. Int J Integr Care. 2010;10:e011. doi:10.5334/ijic.481

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/hiv-aids/cd4-viral-count [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 23]