Translate this page into:

Determination of multipurpose prevention technology choice for contraception and HIV/STI prevention: A survey of sexually active women in Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Margaret O. Ilomuanya, PhD. Department of Pharmaceutics and Pharmaceutical Technology, University of Lagos, Lagos State, Nigeria. milomuanya@unilag.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Ilomuanya MO, Joda AE, Adeyemi OC, et al. Determination of multipurpose prevention technology choice for contraception and HIV/STI prevention: A survey of sexually active women in Nigeria. Am J Pharmacother Pharm Sci 2024:6.

Abstract

Objectives:

Interest in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prophylaxis in the context of multiple sexual and reproductive health risks women face suggests a place for multipurpose prevention techniques (MPTs), which act by combining contraception and pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV into one unified delivery method. At present, condoms are a readily available form of MPTs. The study aims to determine the sexual characteristics of women in Nigeria and assess factors associated with MPT acceptance in the identified population.

Materials and Methods:

An online cross-sectional survey was conducted using the data collection tool Google Forms®. The survey was distributed to the prospective respondents using the snowballing technique through an instant messaging application to ensure proper circulation among the geopolitical zones in Nigeria. Interest in MPT’s was evaluated using descriptive analysis. Specifically, personal and product attributes were evaluated descriptively (frequency and response rating) and with inferential statistics (logistic regression and model validation).

Results:

More than one-half (57%) of the participants were sexually active in the past three months. Most of the subjects reported at least one HIV risk behavior such as engaging in sexual intercourse with a male partner without a condom (50%). Factors associated with acceptance of MPTs included perceived safety, long-lasting action, and effectiveness of the formulation. Formulation types preferred by respondents include daily pills (21%), vaginal gels (12%), and inserts (8%). Personal characteristics supporting MPT use include age (30–39) and (40–49) years, married, formally educated, being a housewife, and having not had sexual intercourse with an HIV-positive male partner and having had an unintended pregnancy.

Conclusion:

Most of the respondents were interested in MPTs as a daily pill. Safety, long-lasting activity, and effectiveness are the top three criteria predicting acceptance. A variety of MPTs are required to be developed to suit the varying needs of different populations. The MPT preferences must be considered during product development to promote future acceptance among women in Nigeria.

Keywords

Human immunodeficiency virus prevention

Sexually transmitted infections

Contraception

Multipurpose prevention technology

INTRODUCTION

Interest in contraception and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prophylaxis in the context of multiple sexual and reproductive health risks women face suggests a place for multipurpose prevention techniques (MPTs). The MPTs are designed to protect patients from unintended pregnancy, HIV, and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) by combining contraception and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into one unified delivery method.[1-4] Male and female condoms are currently the most basic and readily available forms of MPTs.[5,6] Nigeria’s 2 million plus people living with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) ranks her the second largest country with an HIV epidemic in the world including one of the highest transmission rates in the world with UNAIDS estimating that it accounted for over two-thirds of new infections in the West and Central Africa regions.[7,8] About 80% of this infected population reportedly contracted HIV after unprotected heterosexual contact with women being disproportionately affected. Risks of exposure for women include their anatomy as well as a multifactorial disadvantage when negotiating for safe sexual practices.[8] The previous studies have shown that various factors affect women’s acceptance and adherence to contraception including MPTs. Therefore, it is crucial that as the development of MPTs continues, we compare it with other modern contraceptives being used voluntarily and persistently. In evaluating contraception choices, the essential characteristics of women include effectiveness, safety, affordability, long-lasting effects, and whether the method was “forgettable.”[9] The MPT development is centered around discrete female products, thus ensuring that vaginally delivered products such as gels, rings, and inserts are more favorable due to the availability and the ability of women to use them without partner knowledge.[10,11] Another concern that beguiles women is the availability of MPT products that lack hormonal activity, as it will present a safer option for most women, who inadvertently react to hormonal contraceptives. To date, only condoms serve this purpose, and their use is largely dependent on the male partner’s consent, hence taking the decision out of the hands of the female. This issue serves to indicate that more novel MPTs are required and an assessment of women’s reactions to their use is an unexplored parameter. Despite conjecture regarding factors related to the acceptance of MPTs, there has been no specific research on the level of interest in MPTs and factors that would increase their acceptance among women in Nigeria. This study aims to determine the sexual characteristics of women in Nigeria and assess product factors associated with MPT acceptance among the identified interested individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a cross-sectional survey exploring the interest in MPTs among heterosexual women (aged 18–59 years) living in Nigeria. The survey is a representative sampling from all geo-political zones since cultural norms and demographic factors vary across the six zones. To estimate sample size, authors assumed a 95% level of confidence, a 5% margin of error, and estimated incidence of MPTs at 50%;[12,13] this yielded a sample size estimate of 384 respondents.[12]

A pretested data collection tool was utilized for this study. This tool was previously validated by Hynes et al.[13]The data collection tool (questionnaire) was developed using Google Forms®, an online mobile tool for creating customized surveys.

It consisted of two parts:

Part 1: Questions exploring the respondent’s sociodemographic data and

Part 2: Questions exploring respondents’ sexual behavior and concerns, contraceptive use history, and factors that will promote their acceptance of MPTs. These questions were developed following a review of the literature.

The survey was delivered to respondents electronically (Google® Forms), and all volunteers received links through WhatsApp. Reminders were sent through WhatsApp, text, and email reminders where feasible. The tool was set to keep all respondents anonymous, ensuring there was no collection of identifying information. The survey was published in the English language and was open to respondents from December 11, 2020, to January 11, 2021.

The researchers shared the web link to the survey through various WhatsApp groups in the six geo-political zones of Nigeria. These groups existed before the study and were formed for community enlightenment purposes.

The authors ensured representation across geo-political zones by monitoring responses and actively inviting women from communities that were underrepresented in the survey. Weekly reminders were sent to the platforms to get as many respondents as possible within the survey period. Eligible participants were heterosexual women (aged 18–59 years) living in Nigeria who had been sexually active in the past three months.

Data management and analysis

Data collected was checked for completeness and pre-analyzed using the FormsApp® tool. Incomplete submissions were regarded as forms submitted where the respondent did not complete the questions exploring the respondent’s sexual behavior and concerns, contraceptive use history, and factors that will promote their acceptance of MPTs; these responses will be discarded.

The response file was exported as a Microsoft Excel file and imported into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21.0 for analysis. Descriptive analysis (frequency, percentages, medians, means, and mode) was employed to summarize the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and responses. Associations of interest were then evaluated using Chi-square for categorical variables and t-tests or Analysis of Variance for continuous variables.

Ethics

The protocol and informed consent forms were approved by the Health and Research Ethics Committee of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi-araba, Lagos (ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/3958). Eligible respondents were provided information about the study through the study link, and if they chose to participate, they indicated their willingness by clicking to continue with the survey questionnaire (mentioned on the consent part of the ethical conduct form). Participants were made aware that should they decide not to continue, their responses would not be recorded if they failed to submit.

RESULTS

The survey was opened between December 11, 2020, and January 11, 2021, during which time 393 respondents participated, the mean age among the respondents was 35.51 years (Standard Deviation ± 8.96). The highest percentage of respondents came from the Southwest (39.1%) while the lowest participation was recorded from Northwest Nigeria. About one-half of the respondents were married or in a relationship; approximately 77% had earned a bachelor’s degree or higher and over three quarters (86%) were currently employed. Moreover, about 46% of the women had been pregnant [Table 1].

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 210 (53.4) | 112 (28.5) | 49 (12.5) | 21 (5.3) | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Geo-political zone | North-central | North-east | North-west | South-east | South-south | South-west | Diaspora | |

| 44 (11.2) | 22 (5.6) | 12 (3.1) | 99 (25.2) | 60 (15.3) | 154 (39.1) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Marital status | Single | Married/In a relationship | Separated/Divorced | Widowed | ||||

| 184 (46.8) | 198 (50.4) | 6 (1.5) | 5 (1.3) | |||||

| Education level | Primary | Secondary | Vocational school | OND | HND/BSc/BA-bachelors | Masters | Doctoral level | |

| 2 (0.5) | 16 (4.1) | 4 (1.0) | 50 (12.7) | 241 (61.3) | 63 (16.0) | 17 (4.3) | ||

| Employment status | Full-time | Part-time | Self-employed | Housewife | Student | |||

| 204 (51.9) | 58 (14.8) | 77 (19.6) | 12 (3.1) | 42 (10.7) | ||||

| Occupation | Healthcare worker | Administrator | Legal profession | Engineer/IT | Farming planner/interior decor | Teacher/Education | Trader | None |

| 188 (47.8) | 38 (9.7) | 11 (2.8) | 11 (2.8) | 20 (5.1) | 47 (12.0) | 52 (13.2) | 26 (6.6) | |

| Monthly Income | $75 and below | $76–$150 | $151–$250 | $251–$500 | $501–$1250 | Above $1250 | Rather not say | |

| 55 (13.9) | 64 (16.3) | 62 (15.8) | 75 (19.1) | 57 (14.5) | 11 (2.8) | 69 (17.6) | ||

| Have you ever been pregnant? | No | Yes | ||||||

| 211 (53.7) | 182 (46.3) | |||||||

| How many pregnancies have you had? | 0-4 | 5-9 | 10 + | Non-response | ||||

| 149 (37.9) | 31 (7.9) | 2 (0.5) | 211 (53.7) | |||||

| How many children do you currently have? | 0-4 | 5-9 | Non-response | |||||

| 174 (44.3) | 8 (2.0) | 211 (53.7) | ||||||

| Interest in MPTs | No | Yes | ||||||

| 55 (14) | 338 (86) |

MPT: Multipurpose prevention technique

Respondents’ Sexual Behaviors and Concerns

More than one-half of the participants were sexually active in the past three months with 57% having engaged in vaginal sex, about 30% in oral sex, and 3% in anal sex with male partners. The majority of the subjects reported at least one HIV risk behavior with one-half of the subjects (50%) having engaged in any kind of sexual intercourse with a male partner without a condom and another 4.6% engaged in sexual intercourse with a casual partner without a condom. Additionally, one-third (32.6%) were unaware of their partners’ HIV status. About 17% had been diagnosed with STIs (e.g., chlamydia [5.3%] and gonorrhea [4.1%]), and approximately one quarter (25%) have had an unintended (unplanned or unexpected) pregnancy. Some proportion of the respondents often worried that they may have been pregnant (15%), while another 4% often worried that they might have contracted HIV [Table 2].

| Variable | Option | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Have you been sexually active with a male partner in the past 3 months? | Rather not say | 11 (2.8) |

| No | 161 (41.0) | |

| Yes | 221 (56.2) | |

| Have you engaged in vaginal sex with a male partner in the last three months? | Rather not say | 8 (2.0) |

| No | 161 (41.0) | |

| Yes | 224 (57.0) | |

| Have you engaged in oral sex with a male partner in the last three months? | Rather not say | 16 (4.1) |

| No | 260 (66.2) | |

| Yes | 117 (29.8) | |

| Have you engaged in anal sex with a male partner in the last three months? | Rather not say | 2 (0.5) |

| No | 379 (96.4) | |

| Yes | 12 (3.1) | |

| In the past three months, have you had any type of sexual intercourse with a casual partner? | Rather not say | 3 (0.8) |

| No | 366 (93.1) | |

| Yes | 24 (6.1) | |

| In the past three months, have you had any kind of sexual intercourse with an HIV-positive male partner? | Rather not say | 9 (2.3) |

| No | 383 (97.5) | |

| Yes | 1 (0.3) | |

| In the past three months, have you engaged in any kind of sexual intercourse with a male partner without a condom? | Rather not say | 5 (1.3) |

| No | 191 (48.6) | |

| Yes | 197 (50.1) | |

| In the past three months, have you engaged in any kind of sexual intercourse with a casual partner without a condom? | Rather not say | 6 (1.5) |

| No | 369 (93.9) | |

| Yes | 18 (4.6) | |

| Are you aware of your partner’s HIV status? | Rather not say | 9 (2.3) |

| No | 128 (32.6) | |

| Yes | 256 (65.1) | |

| Have you had an HIV test done within the past year? | Rather not say | 3 (0.8) |

| No | 193 (49.1) | |

| Yes | 197 (50.1) | |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI)? | Rather not say | 2 (0.5) |

| No | 325 (82.7) | |

| Yes | 66 (16.8) | |

| Have you ever had an unintended (unplanned or unexpected) pregnancy? | Rather not say | 10 (2.5) |

| No | 285 (72.5) | |

| Yes | 98 (24.9) | |

| In the past three months, how often did you worry that you might contract HIV? | Rather not say | 1 (0.3) |

| Never | 274 (69.7) | |

| Rarely | 96 (24.4) | |

| Often | 14 (3.6) | |

| Always | 8 (2.0) | |

| In the past three months, how often did you worry that you might already have HIV? | Rather not say | 4 (1.0) |

| Never | 327 (83.2) | |

| Rarely | 55 (14.0) | |

| Often | 3 (0.8) | |

| Always | 4 (1.0) | |

| In the past three months, how often did you worry that you might contract a STI other than HIV? | Rather not say | 3 (0.8) |

| Never | 253 (64.4) | |

| Rarely | 101 (25.7) | |

| Often | 22 (5.6) | |

| Always | 14 (3.6) | |

| In the past three months, how often did you worry that you might already have an STI other than HIV? | Rather not say | 1 (0.3) |

| Never | 277 (70.5) | |

| Rarely | 93 (23.7) | |

| Often | 15 (3.8) | |

| Always | 7 (1.8) | |

| In the past three months, how often did you worry that you might get pregnant? | Rather not say | 2 (0.5) |

| Never | 185 (47.1) | |

| Rarely | 108 (27.5) | |

| Often | 59 (15.0) | |

| Always | 39 (9.9) | |

| In the past three months, how often did you worry that you might already be pregnant? | Rather not say | 3 (0.8) |

| Never | 206 (52.4) | |

| Rarely | 99 (25.2) | |

| Often | 58 (14.8) | |

| Always | 27 (6.9) | |

| How many lifetime partners have you had in total? | 0 | 92 (23.4) |

| 1–5 | 232 (59.0) | |

| 6–10 | 52 (13.2) | |

| 11–15 | 4 (1.0) | |

| >15 | 13 (3.3) | |

| On a weekly basis, how often do you engage in any act of sexual intercourse? | None | 168 (42.7) |

| Once | 88 (22.4) | |

| Twice | 46 (11.7) | |

| Thrice | 42 (10.7) | |

| Four times | 7 (1.8) | |

| Five times | 1 (0.3) | |

| More than 5 times | 5 (1.3) | |

| Rather not say | 36 (9.2) | |

| STI diagnosed? | Chlamydia | 21 (5.3) |

| Gonorrhea | 16 (4.1) | |

| Syphilis | 9 (2.3) | |

| Trichomoniasis | 7 (1.8) | |

| HPV | 6 (1.5) | |

| Herpes | 4 (1.0) | |

| HIV | 3 (0.8) | |

| Non-response | 327 (83.2) |

STI: Sexually transmitted infection, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus

Contraceptive use history

About two-thirds of the respondents were not hoping to get pregnant at the time of the study (67%). About 60% of the respondents never use any form of birth control during sexual intercourse, and only 16% indicated that they use it all time. Most of the respondents that do not use any method of contraception indicated that they do not think that they need to use any method (15%), about 8% think that the methods are not safe and are designed to make women sterile (8%) while 7% do not know that they need to use any method, the husband does not believe in them and do not believe they work. For their last sexual encounter, only about 24% used a condom [Table 3].

| Variable | Option | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Are you currently hoping/planning to get pregnant? | Rather not say | 19 (4.8) |

| No | 262 (66.7) | |

| Yes | 112 (28.5) | |

| In the past 3 months, how often did you use any form of birth control during sexual intercourse? | Never | 235 (59.8) |

| Rarely | 56 (14.2) | |

| Some of the time | 25 (6.4) | |

| Most of the time | 13 (3.3) | |

| All the time | 64 (16.3) | |

| Select your reasons for not using any form of birth control during sexual intercourse. (if not all the time) | I don’t believe they work | 28 (7.1) |

| My husband does not believe in them | 29 (7.4) | |

| Our religion does not accept them | 23 (5.9) | |

| Our culture does not support their use | 25 (6.4) | |

| The methods are not safe | 30 (7.6) | |

| The methods are designed to make women sterile | 30 (7.6) | |

| They are too expensive | 26 (6.6) | |

| I do not know if I need to use any method | 28 (7.1) | |

| I do not think I need to use any method | 58 (14.8) | |

| We are currently trying to have a child | 52 (13.2) | |

| Nonresponse | 64 (16.3) | |

| Did you (or your partner) use a condom the last time you had sexual intercourse? | Rather not say | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 300 (76.3) | |

| Yes | 93 (23.7) |

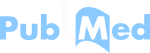

The chosen contraception from the respondents is depicted in Figure 1. Condoms were the most favorite whether mostly used (34%), used in the past three months (27%) or the week before the survey (22%). Condoms were followed by birth control pills for mostly used (17%) and use in the past three months (11%), but for use in the week before the survey, the withdrawal method came in second at 14%. The most used form of contraception was shown to be no method used at (15%), withdrawal method (11%), and intrauterine device (7%).

- Forms of contraception used by the respondent by categories.

Factors associated with acceptance of MPTs

Factors influencing the future acceptance of MPTs are shown in Table 4 Product safety, effectiveness at preventing infections with other STIs, long-lasting, effectiveness at preventing infection with HIV, affordability, the possibility of privacy, and effectiveness at preventing pregnancy were all highly rated. Therefore, MPTs deemed to be most acceptable must be safe, long-lasting, effective at protecting against STIs including HIV, and affordable.

| Mean Response Rating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The extent of Influence of | Mean | SD | Relative Mean | Extent |

| Safety | 2.83 | 0.483 | 1.12 | High |

| Effective at preventing infections with other STIs | 2.74 | 0.553 | 1.08 | High |

| Long-lasting | 2.74 | 0.568 | 1.08 | High |

| Effective at preventing infection with HIV | 2.69 | 0.603 | 1.06 | High |

| Product is affordable (low cost) | 2.66 | 0.589 | 1.05 | High |

| Privacy (nobody needs to know you are on a method) | 2.63 | 0.661 | 1.04 | High |

| Effective at preventing pregnancy | 2.53 | 0.710 | 1.00 | High |

| Partners’ opinion | 2.48 | 0.696 | 0.98 | Low |

| Do not need to remember to take or use the method regularly | 2.43 | 0.711 | 0.96 | Low |

| Partners’ consent | 2.40 | 0.737 | 0.95 | Low |

| Method gives side effects | 2.36 | 0.828 | 0.94 | Low |

| Having monthly periods while using it | 2.28 | 0.787 | 0.90 | Low |

| Product is free | 2.06 | 0.760 | 0.82 | Low |

| Overall mean | 2.53 | 0.363 | 1.00 | |

Sample size: 393. SD: Standard Deviation, RM: Relative Mean. (RM≥1 = High, RM<1 = Low). Scale: 3: Very important; 2: Somewhat important; 1: Not important. STI: Sexually transmitted infection, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, MPT: Multipurpose prevention technique

The respondents seemed to prefer daily pills (21%) to vaginal gels (12%) and inserts (8%) as shown in Table 5. Other variations of interest in pills show that weekly (12%), monthly (26%), or quarterly pill-taking (37%) are also acceptable options. About 56% of the respondents prefer the on-demand use of MPTs rather than having them on constantly (44%).

| Variable | Option | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Options you would be interested in using for protection against HIV | Daily pills | 82 | 20.9 |

| Vaginal gels | 45 | 11.5 | |

| Vaginal insets that I can insert and remove myself | 32 | 8.1 | |

| Vaginal ring that I can insert and remove myself | 19 | 4.8 | |

| Injection that I can administer myself | 30 | 7.6 | |

| Injection that would be administered to me by others | 31 | 7.9 | |

| Implant that is placed for me | 33 | 8.4 | |

| Blank | 121 | 30.8 | |

| Proportion more interested in a method of protection against HIV if the method were combined with contraception? | Rather not say | 187 | 47.6 |

| No | 63 | 16.0 | |

| Yes | 143 | 36.4 | |

| If pills are preferred but not daily, what would be your preferred dosing interval? | Weekly | 48 | 12.2 |

| Monthly | 102 | 26.0 | |

| Every 3 months | 146 | 37.2 | |

| Not sure | 83 | 21.1 | |

| Other: | 14 | 3.6 | |

| Which is the most important consideration in a prevention method? | Use or insert protection only when I want to have sexual intercourse | 219 | 55.7 |

| Use it or have it on constantly | 174 | 44.3 |

PrEP: Pre-exposure prophylaxis, MPT: Multipurpose prevention technique, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus

Predictive personal characteristics of the women that indicate interest in MPTs are listed in Table 6. Twenty-two (22) predictors were initially included in a multivariable logistic regression model. The logistic regression was used to adjust for confounding variables. Through the backward stepwise elimination method, 15 predictors were eliminated from the multivariate model as they were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). After elimination, the excluded predictors were reinserted into the final model to further check whether they became statistically significant. Finally, seven predictors remained in the final model.

| Predictors | B Coefficients | Wald | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||||

| 18–29 | 27.373 | 0.000* | ||

| 30–39 | 1.895 | 18.943 | 6.655 (2.834, 15.627) | 0.000* |

| 40–49 | 3.698 | 17.650 | 40.369 (7.191, 226.626) | 0.000* |

| 50–59 | 20.895 | 1.002 | 118.654 (57.674, 179.634) | 0.998 |

| 60+ | −1.123 | 0.098 | 0.325 (0.000, 0.650) | 1.000 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 36.005 | 0.000* | ||

| Married | 3.032 | 36.005 | 20.738 (7.703, 55.830) | 0.000* |

| Separated/Divorced | 21.372 | 1.075 | 191.884 (15.000, 368.768) | 0.999 |

| Widowed | 20.581 | 1.030 | 86.761 (17.786, 155.736) | 0.999 |

| Education level | ||||

| Informal education | 10.091 | 0.018* | ||

| Formal education | 6.956 | 9.491 | 2.602 (1.416-4.782) | 0.002* |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full-time employment | 10.693 | 0.030* | ||

| Part time employment | -0.611 | 1.019 | 0543 (0.166, 1.777) | 0.313 |

| Self-employed | −0.691 | 1.974 | 0.501 (0.191, 1.314) | 0.160 |

| Housewife | 2.276 | 3.906 | 0.735 (0.451, 1.019) | 0.048* |

| Student | −2.105 | 4.062 | 0.122 0.016, 0.944) | 0.044* |

| In the past three months, have you had any kind of sexual intercourse with an HIV-positive male partner? | 6.672 | 0.036* | ||

| No | 3.693 | 6.672 | 40.165 (2.437, 661.900) | 0.010* |

| Yes | 7.382 | 0.000 | 160.478 (112.004, 208.952) | 1.000 |

| Have you ever had an unintended (unexpected) pregnancy? | 49.098 | 0.000* | ||

| No | −1.049 | 0.687 | 0.350 (0.029, 4.188) | 0.407 |

| Yes | 3.287 | 5.669 | 26.752 (1.788, 400.264) | 0.017* |

| Are you currently hoping/planning to get pregnant? | 8.044 | 0.018* | ||

| No | 0.260 | 0.090 | 1.296 (0.239, 7.045) | 0.764 |

| Yes | −0.971 | 1.172 | 0.379 (0.065, 2.195) | 0.279 |

| Constant | −6.285 | 8.459 | 0.002 | 0.004* |

Model Summary: Nagelkerke R Square=0.798, Omnibus test of model coefficients: Chi-square value=357.623 (P<0.05). Hosmer and Lemeshow Test: Chi-square value=8.339, Sig.=0.401, Overall percentage prediction=91.3% > 50.0%. Method of Variable Removal=Backward Stepwise (Likelihood Ratio). *Significant at 5% level. OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus

The logistic regression results indicated that: Age, marital status, education level, employment status, and responses to the following questions “In the past three months, have you had any kind of sexual intercourse with an HIV-positive male partner?,” “Have you ever had an unintended (unplanned or unexpected) pregnancy?” and “Are you currently hoping/planning to get pregnant?” have a significant influence on interest in MPTs among women at Wald = 27.373, 36.005, 10.091, 10.693, 6.672, 49.094, and 8.044, since P < 0.05, respectively.

The significant variables are specifically interpreted by studying the results of the odds ratio (OR) using the first group of each categorical variable as an indicator or reference. The results revealed that women aged 30–39 years (OR 6.655; confidence interval [CI] 2.834, 15.627), 40–49 years (OR 40.369; CI 7.191, 226.626), women who are married (OR 20.738; CI 7.703, 55.830), formally educated women (OR 2.602; 95% CI 1.416, 4.782), women who have not had the risk of sexual intercourse with an HIV-positive male partner (OR 40.165; CI 2.437, 661.900), and women who have had a high self-perceived risk of unintended or unexpected pregnancy (OR 26.752; CI 1.788, 400.264) are more likely to have interest in MPTs.

On the other hand, in terms of employment status, housewives and students (OR 0.735; CI 0.451, 1.019 and (OR 0.122; CI 0.016, 0.944) and women who are planning to get pregnant (OR 0.379; CI 0.065, 2.195) are less likely to be interested in MPTs.

The model implies that a unit increase in women aged (30–39) years and (40–49) years, married women, formally educated women, women who are housewives, women who have not had any form of sexual intercourse with an HIV-positive male partner, and women who have had an unintended pregnancy have an increased interest in MPTs by the respective estimated coefficients.

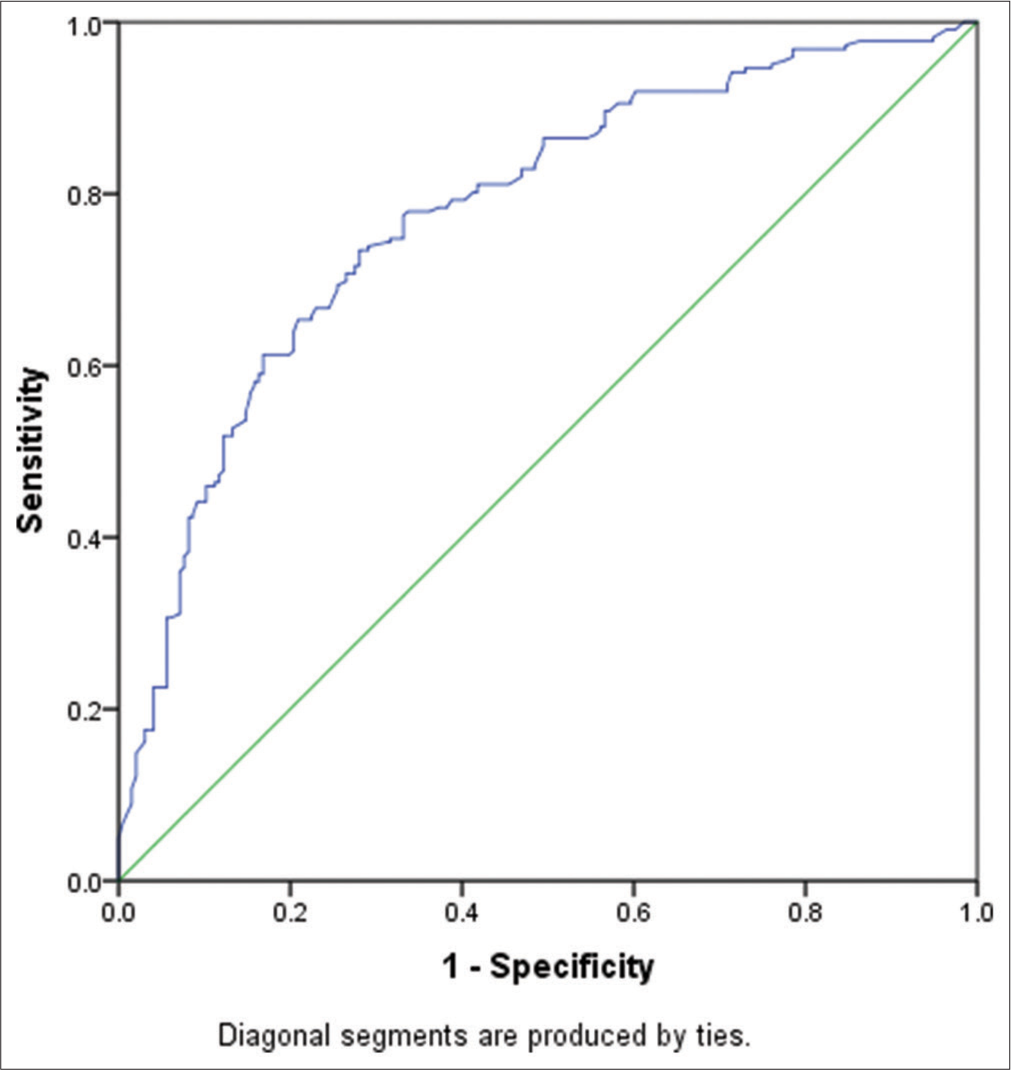

Model validation

Model assessment and goodness-of-fit were performed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and Nagelkerke R squared. The Nagelkerke R squared= 0.798 (i.e., the model explained 79.8% of the variance of interest) in MPTs, which suggests a good prediction power. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test at Chi-square value = 8.339 (P < 0.05) for this model showed good agreement between the predicted and observed values with 95% of the imputed datasets and, therefore, supports the model’s adequacy for fitting the data. It had adequate prediction power, supported by the overall percentage prediction of 91.3, which indicated that about 91.3% of the cases were correctly classified or predicted by the model at a 0.50 (50.0%) cutoff value [Figure 2]. That is, the model is correct at Chi-square value = 357.623 (P < 0.05), about 9 out of 10 times in predicting interest in MPTs. The performance of the model was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) based on the saved predicted probabilities. The ROC = 0.780 (95% CI 0.735–0.824) [Table 7], hence, was able to discriminate between women who are interested and those who are not interested in MPTs. The ROC curve is a visual index of the accuracy of interest in MPTs. The further the curve lies above the reference line, the more accurate the test, which can be easily observed from the ROC curve. The model was correctly specified and had an adequate ability to distinguish between individuals who are interested in MPTs and those who are not.

| Test result variable (s): Predicted probability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Std. Errora | P-valueb | 95% CI | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| 0.780 | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0.735 | 0.824 |

The test result variable (s): Predicted probability has at least one tie between the positive actual state group and the negative actual state group. aUnder the nonparametric assumption. bNull hypothesis: true area=0.5. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic, CI: Confidence interval

- Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) based on the saved predicted probabilities.

DISCUSSION

Very few women are practicing informed safer sex and HIV self-testing consistently with their partners in Nigeria compared to the intended targets (95-95-95 target for treatment: 95% of people living with HIV know their HIV status; 95% of people know their status on treatment; and 95% of people on treatment with suppressed viral loads) for stopping HIV transmission.[13-15] Although this has been incorporated into the national HIV and AIDS strategic framework, many women are unaware of their partner’s HIV status and may not know to protect themselves adequately or know they should use contraceptives consistently.[16-18] Although HIV self-testing is easy to use, discrete, available, and promotes partner cotesting, benefits to the general population may be limited by lack of adoption. Health infrastructure deficits, multidimensional poverty, and multifactorial inhibitors are barriers that continue to reduce the impact of these interventions.[19].

Many women in this study may have overestimated their own health safety. For example, more women reported condomless sex than those who reported being worried (at least “often”) about contracting HIV, STIs or becoming pregnant. This consideration is consistent with the low STI testing reported by respondents. Sexually active women aged 30–50 years, who had formal education, did not have a discordant partner and had a high self-perceived risk of unintended pregnancy are more likely to have an interest in MPTs. In a previous study, Hynes et al. found no association between age, self-perceived HIV risk factors, and interest in MPTs among sexually active women in the US.[13] There is still a high preponderance of condomless sexual contact exposing many females to sexual and reproductive health risks. This risk exacerbates the already higher biological risk for HIV transmission that women suffer.[14,15] In many African countries, sociocultural norms, values, the power imbalance between men and women, and practices that promote gender inequality may contribute to the continued high prevalence of risky sex practices. These barriers and challenges also contribute to the generally poor uptake of modern contraceptives among women, adherence, and consistency.

There is a high unmet need for contraceptives among sexually active women (respondents) in this study (26.5%). Women are said to have an unmet contraceptive need if they say, they would prefer to avoid a pregnancy but are not using a contraceptive.[20] This is higher than the reported 16% of the NDHS, a more representative survey.[21] Condoms were the most used form of contraception reported by respondents in all-time considerations, similar to NDHS survey reports in 2008 and 2013.[21] This may be related to the multiple benefits associated with its use (e.g., STI protection and pregnancy prevention). Condoms can be used discreetly, are effective when used appropriately, are widely available without medical consultation, and have a lower cost for acquisition and lower medical risk for adverse effects. It should also be noted that in recent studies with sexually active youth in Nigeria, the continued high prevalence of this method was attributed by youth to sociocultural bias, discrimination, and the unwillingness of providers (including gatekeepers) to provide long-acting reversible contraception services to youth.[22] Barriers to the adoption of modern contraceptives reported in this study align with those reported by Durowade et al. and Asekun-Olarinmoye et al.[23,24] They include religious bias, partner resistance, sociocultural issues, gaps in knowledge of contraceptives, and costs. Several interventions have been implemented by the government and partners to address these barriers- from behavioral change communication to providing free contraceptives in public health facilities. However, for various reasons including poor health infrastructure, poor funding, and lack of political will, the effect of the interventions has been limited.

In our study, 86% of respondents reported an interest in using MPTs when they become available. The enthusiasm is similar to the 83% reported by Hynes et al. among sexually active women in the US.[13] This number is, however, lower than the 96% reported by Minnis et al.[25] Participants in the study by Minnis et al. reported that the simplicity, ease of use, stress, and protection against unforeseen events (e.g., rape, partner infidelity, and condom failure) of MPTs make them desirable.[25] This desirability, as in this study, was moderated by concerns for safety, sociocultural norms, and biases. Respondents in this study reported safety as the most important consideration for adopting an MPT. This is aligned with the global properties Brady and Tolley posit that may improve the desirability for MPTs over other methods.[26] Safety and other considerations identified are similar to the elicited barriers to the adoption of modern contraceptives reported by respondents. It is, therefore, important to recognize that developing MPTs without addressing the existing barriers may only result in product substitution and not improve adoption overall.

Respondents also appeared to have rated desirability for prevention of STIs, cost, and duration of action (probably for discreteness of method) over the prevention of pregnancy. Moreover, of interest is that this study found the influence of partners’ opinions and consent to a low influence. This is interesting since, in Nigerian families, sociocultural norms and practices keep women in a lower power dynamic than their partners.[22] What this signifies is that with increasing privacy, women may indeed be able to disregard their partner’s disapproval and adopt discrete, long-lasting MPTs. Respondents reported interest in using MPTs with daily pills ranking the highest among these products. The preference for everyday pills could stem from the awareness, widespread use of oral contraceptive pills, perceived safety profile of the method, and the perceived ease for the female to maintain control of the choice of MPT without the male partner’s permission pills.[27-29] This buttresses research supporting the inclusion of PrEP with oral contraceptives for dual protection against both HIV and unplanned pregnancies.[30,31] Vaginal rings and inserts had lower ratings, and self-administered injections had the lowest rating of interest when compared with pills. However, these findings are inconsistent with the report by Hynes et al. where the most preferred formulations for delivery of PrEP and MPT among women in the US were long-acting injections.[32]

On-demand protection from HIV, STIs, and unplanned pregnancies was preferred over constant use of MPT. A wide range of research has developed these on-demand products ranging from vaginal rings, freeze-dried inserts, microspheres, gels, etc.[5,33,34] The limitations arising from coital dependency and user dependency of some of the methods were seen to affect the choice of on-demand MPTs. In evaluating product factors associated with future acceptance, the mean response ratings for safety, effectiveness, privacy, and affordability were very high. The respondents were, however, more concerned with efficacy than side effects arising from MPT use. The affordability of MPTs is critical to the uptake of the product by consumers. It is estimated that 150 million Nigerians live on less than $2 per day, according to the African Development Bank in its Nigerian economic outlook.[35] Hence, the affordability of an MPT product is critical to its uptake. The Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health, working with the Society for Family Health, provides heavily subsidized birth control medications comprising long-acting injections, IUDs, etc. The HIV treatments, PEP and PrEP are also offered to clients at no cost.[35] Hence, when MPTs become available, it will be necessary to integrate their use within the current framework utilized to encourage women to adopt them at no more than the current costs of between $0.5 and $20/month.[36] The overall study population was able to relate to an MPT that mimicked their preferred contraceptive dosage form; hence, the daily pill as an MPT could be deemed the most preferred option in the population studied.

Limitations of the study

This study, by design excluded sexually active women, who could not access the study information or an online survey tool (Google forms®). With the widespread use of WhatsApp in Nigeria, the tendency to recruit these women in a paper-based survey may be low and impractical for the duration and budget available for this survey. We also allege that there could have been some recall bias when respondents were asked to restate their considerations for choosing a modern contraceptive method. The use of WhatsApp groups linked to the researchers or their extended contacts for distributing the survey could introduce network bias, as it limits participants to a specific social network.

CONCLUSION

The factors that support the future use of MPTs among women in Nigeria include product safety, long-lasting effectiveness at preventing STIs and pregnancy, affordability, and the possibility of privacy. Most of the respondents will prefer MPTs formulated as pills compared to gels, inserts, or injections. The model implies that a unit increase in women aged (30–39) years and (40–49) years, married women, formally educated women, women who are housewives, women who have not had any kind of sexual intercourse with an HIV-positive male partner, and women who have had an unintended pregnancy will have increase interest in MPTs by the respective estimated coefficients. A future direction for the study would be to identify and develop products based on the suggestions from the respondents working towards either ensuring product costs are affordable or developing policies alongside to improve access.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Barbara Friedland and Lisa Haddad of the Center for Biomedical Research, Population Council, NY, USA, for their valuable insights during research design as well as in the manuscript preparation.

Data availability

The data generated during or analyzed during this study is not publicly available to protect patient privacy. Data is available for researchers, who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Authors’ contributions

MOI and AEJ originated the study concept and design, OCA, AA, OO, and CSI conducted the literature search, and AA, OCA, and AEJ were responsible for the data acquisition and analysis. All authors agreed on the definition of intellectual content, and all participated in manuscript preparation, editing, and review.

Ethical approval

The study was exempted from full review via a notice with Health Research Committee Assigned number of ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/3958.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

References

- Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001-2008. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S1):S43-S48. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2013.301416

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75181/1/9789241503839_eng.pdf?ua=12012 [Last accessed on 2023 Dec 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV Surveillance Report 2015. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf [Last accessed on 2021 Nov 30]

- [Google Scholar]

- We are not the same": African women's view of multipurpose prevention products in the TRIO clinical study. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:97-107. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S185712

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multipurpose prevention technologies for sexual and reproductive health: Mapping global needs for introduction of new preventive products. Contraception. 2016;93:32-43. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.09.002

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Male and female condoms: Their key role in pregnancy and STI/HIV prevention. Best Pract Res Clin Obst Gynaecol. 2020;66:55-67. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.12.001

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identifying and prioritizing implementation barriers, gaps, and strategies through the Nigeria Implementation Science Alliance: Getting to zero in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72:S161-S166. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000001066

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV and AIDS in Nigeria - avert. 2021. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/nigeria [Last accessed on 2021 May 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PREP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. Aids Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:102-110. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0142

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development of trigger sensitive hyaluronic acid/palm oil-based organogel for in vitro release of HIV/AIDS microbicides using artificial neural networks. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2020;6:1. doi: 10.1186/s43094-019-0015-8

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15-44: United States, 2011-2013. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;86:1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2004. Seattle: Raosoft. Inc.; Available from: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html [Last accessed on 2023 Dec 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Interest in multipurpose prevention technologies to prevent HIV/STIs and unintended pregnancy among young women in the United States. Contraception. 2018;97:277-284. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.006

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term consistent use of a vaginal microbicide gel among HIV-1 sero-discordant couples in a phase III clinical trial (MDP 301) in rural southwest Uganda. Trials. 2013;14:33. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-33

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biological factors that place women at risk for HIV: Evidence from a large-scale clinical trial in Durban. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16:19. doi: 10.1186/s12905-016-0295-5

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles to go-closing gaps, breaking barriers, righting injustices In: Global AIDS update. United States: United Nations Fund for Population Activities; 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fast-track: Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- Revised national HIV and AIDS strategic framework 2019-2021 Abuja: Nigeria National Agency for the Control of AIDS; 2019.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why does uptake of family planning services remain suboptimal among Nigerian women? A systematic review of challenges and implications for policy. Contracept Reprod Med. 2020;5:30. doi: 10.1186/s40834-020-00133-6

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2007. New York: Guttmacher Institute; Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/2007/07/09/or37.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Dec 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Demand and unmet needs of contraception among sexually active In-Union women in Nigeria: Distribution, associated characteristics, barriers, and program implications. SAGE Open. 2018;8:215824401775402. doi: 10.1177/2158244017754023

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A cross-country qualitative study on contraceptive method mix: Contraceptive decision making among youth. Reprod Health. 2021;18:105. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01160-5

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to contraceptive uptake among women of reproductive age in a semi-urban community of Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27:121-128. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v27i2.4

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to use of modern contraceptives among women in an inner city area of Osogbo metropolis, Osun State, Nigeria. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:647-655. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s47604

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giving voice to the end-user: Input on multipurpose prevention technologies from the perspectives of young women in Kenya and South Africa. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2021;29:246-260. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2021.1927477

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aligning product development and user perspectives: Social-behavioural dimensions of multipurpose prevention technologies. BJOG. 2014;121:70-78. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12844

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes and acceptance of oral and parenteral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among potential user groups: A multinational study. PLOS One. 2012;7:e28238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028238

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes and program preferences of African-American urban young adults about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PREP) Aids Educ Prev. 2012;24:408-421. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.5.408

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racial differences and correlates of potential adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis: Results of a national survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 1):S95-S101. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182920126

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favoring “peace of mind”: A qualitative study of African women's HIV prevention product formulation preferences from the MTN-020/ASPIRE trial. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31:305-314. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0075

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Estimating the market size for a dual prevention pill: adding contraception to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to increase uptake. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2020;47:166-172. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200662

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preferred product attributes of potential multipurpose prevention technologies for unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections or HIV among U.S. women. J Womens Health. 2019;28:665-672. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7001

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffithsin carrageenan fast dissolving inserts prevent SHIV HSV-2 and HPV infections in vivo. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3881. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06349-0

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development and evaluation of mucoadhesive bigel containing tenofovir and maraviroc for HIV prophylaxis. Fut J Pharm Sci. 2020;6:81. doi: 10.1186/s43094-020-00093-3

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigerian Economic Outlook. 2020. Available from: https://www.afdb.org/en/countries-west-africa-nigeria/nigeria-economic-outlook [Last accessed on 2023 Dec 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017. Nigeria: Task-sharing provision of injectable contraceptives and implants with community health extension workers; Available from: https://www.e2aproject.org/wp-content/uploads/tech-brief-task-sharing-akwa-ibom-nigeria-final.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Dec 20]

- [Google Scholar]